[ Back ] [ Up ] [ Next ]

Chapter 3

The Authority of the Sunnah: Its Historical Aspect

Faced with the overwhelming arguments in favour of the authority

of sunnah, some people resort to another way of suspecting its

credibility, that is, to suspect its historical authenticity.

According to them, the sunnah of the Holy Prophet ( ) though

having a binding authority for all times to come, has not been preserved in a

trustworthy manner. Unlike the Holy Qurān, they say, there is no single book

containing reliable reports about the sunnah. There are too many works

having a large number of traditions sometimes conflicting each other. And these

books, too, were compiled in the third century of Hijrah. So, we cannot place

our trust in the reports which have not even been reduced to writing

during the first three centuries.

) though

having a binding authority for all times to come, has not been preserved in a

trustworthy manner. Unlike the Holy Qurān, they say, there is no single book

containing reliable reports about the sunnah. There are too many works

having a large number of traditions sometimes conflicting each other. And these

books, too, were compiled in the third century of Hijrah. So, we cannot place

our trust in the reports which have not even been reduced to writing

during the first three centuries.

This argument is based on a number of misstatements and

misconceptions. As we shall see in this chapter, inshā-Allāh, it is

totally wrong to claim that the traditions of the sunnah have been

compiled in the third century. But, before approaching this historical aspect of

the sunnah, let us examine the argument in its logical perspective.

This argument accepts that the Holy Prophet ( )

has a prophetic authority for all times to come, and that his obedience is

mandatory for all Muslims of whatever age, but in the same breath it claims that

the reports of the sunnah being unreliable, we cannot carry out this

obedience. Does it not logically conclude that Allāh has enjoined upon us to

obey the Messenger, but did not make this obedience practicable. The question is

whether Allāh Almighty may give us a positive command to do something which is

beyond our ability and means. The answer is certainly no. The Holy Qurān

itself says,

)

has a prophetic authority for all times to come, and that his obedience is

mandatory for all Muslims of whatever age, but in the same breath it claims that

the reports of the sunnah being unreliable, we cannot carry out this

obedience. Does it not logically conclude that Allāh has enjoined upon us to

obey the Messenger, but did not make this obedience practicable. The question is

whether Allāh Almighty may give us a positive command to do something which is

beyond our ability and means. The answer is certainly no. The Holy Qurān

itself says,

Allāh does not task anybody except to his ability.

It cannot be envisaged that Allāh will bind all the people with

something which does not exist or cannot be ascertained. Accepting that Allāh

has enjoined upon us to follow the sunnah of the Holy Prophet ( ),

it certainly implies that the sunnah is not undiscoverable. If Allāh has

made it obligatory to follow the sunnah, He has certainly preserved it

for us, in a reliable form.

),

it certainly implies that the sunnah is not undiscoverable. If Allāh has

made it obligatory to follow the sunnah, He has certainly preserved it

for us, in a reliable form.

The following aspect also merits consideration. Allāh Almighty

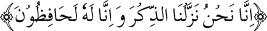

has given us a promise in the Holy Qurān:

Indeed We have revealed the Zikr (ie. the Qurān) and surely

We will preserve it. (15:9)

In this verse, Allāh Almighty has assured the preservation of

the Holy Qurān. This implies that the Qurān will remain uninterpolated

and that it shall always be transferred from one generation to the other in its

real and original form, undistorted by any foreign element. The question now is

whether this divine protection is restricted only to the words of the Holy

Qurān or does it extend to its real meanings as well. If the prophetic

explanation is necessary to understand the Holy Qurān correctly, as proved

in the first chapter, then the preservation of the Qurānic words alone

cannot serve the purpose unless the prophetic explanations are also preserved.

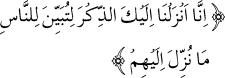

As quoted earlier, the Holy Book says,

We have revealed to you the Zikr (Qurān) so that you may

explain to the people what has been sent down for them.

The word Zikr has been used here for the Holy

Qurān as has been used in the verse 15:9 and it has been made clear that the

people can only benefit from its guidance when they are led by the explanations

of the Holy Prophet ( ).

).

Again, the words for the people indicate (especially in

the original Arabic context), that the Holy Prophets ( )

explanation is always needed by everyone.

)

explanation is always needed by everyone.

Now, if everyone, in every age is in need of the prophetic

explanation, without which they cannot fully benefit from the Holy Book, how

would it be useful for them to preserve the Qurānic text and leave its

prophetic explanation at the mercy of distorters, extending to it no type of

protection whatsoever.

Therefore, once the necessity of the prophetic explanations of

the Holy Qurān is accepted, it will be self-contradictory to claim that

these explanations are unavailable today. It will amount to negating the divine

wisdom, because it is in no way a wise policy to establish the necessity of the sunnah

on the one hand and to make its discovery impossible on the other. Such a policy

cannot be attributed to Allāh, the All-Mighty, the All-Wise.

This deductive argument is, in my view, sufficient to establish

that comprehending the sunnah of the Holy Prophet ( ),

which is necessary for the correct understanding of the divine guidance, shall

as a whole remain available in a reliable manner forever. All objections raised

against the authenticity of the sunnah as a whole can be repudiated on

this score alone. But in order to study the actual facts, we are giving here a

brief account of the measures taken by the ummah to preserve the sunnah

of the Holy Prophet (

),

which is necessary for the correct understanding of the divine guidance, shall

as a whole remain available in a reliable manner forever. All objections raised

against the authenticity of the sunnah as a whole can be repudiated on

this score alone. But in order to study the actual facts, we are giving here a

brief account of the measures taken by the ummah to preserve the sunnah

of the Holy Prophet ( ).

It is a brief and introductive study of the subject, for which the comprehensive

and voluminous books are available in Arabic and other languages. The brief

account we intend to give here is not comprehensive. The only purpose is to

highlight some basic facts which, if studied objectively, are well enough to

support the deductive inference about the authenticity of the sunnah.

).

It is a brief and introductive study of the subject, for which the comprehensive

and voluminous books are available in Arabic and other languages. The brief

account we intend to give here is not comprehensive. The only purpose is to

highlight some basic facts which, if studied objectively, are well enough to

support the deductive inference about the authenticity of the sunnah.

The Preservation of Sunnah

It is totally wrong to say that the sunnah of the Holy

Prophet ( )

was compiled for the first time in the third century. In fact, the compilation

had begun in the very days of the Holy Prophet (

)

was compiled for the first time in the third century. In fact, the compilation

had begun in the very days of the Holy Prophet ( )

as we shall see later, though the compilations in a written form were not the

sole measures adopted for the preservation of the sunnah. There were many

other reliable sources of preservation also. In order to understand the point

correctly we will have to know the different kinds of the sunnah of the

Holy Prophet (

)

as we shall see later, though the compilations in a written form were not the

sole measures adopted for the preservation of the sunnah. There were many

other reliable sources of preservation also. In order to understand the point

correctly we will have to know the different kinds of the sunnah of the

Holy Prophet ( ).

).

Three Kinds of Ahādīth

An individual tradition which narrates a sunnah of

the Holy Prophet ( )

is termed in the relevant sciences as hadīth (pl. ahādīth).

The ahādīth, with regard to the frequency of their sources, are divided

into three major kinds:

)

is termed in the relevant sciences as hadīth (pl. ahādīth).

The ahādīth, with regard to the frequency of their sources, are divided

into three major kinds:

(1) Mutawātir: It is a hadīth narrated in each era, from the days of the Holy Prophet ( )

up to this day by such a large number of narrators that it is impossible to

reasonably accept that all of them have colluded to tell a lie.

)

up to this day by such a large number of narrators that it is impossible to

reasonably accept that all of them have colluded to tell a lie.

This kind is further classified into two sub-divisions:

(a) Mutawātir in words: It is a hadīth

whose words are narrated by such a large number as is required for a mutawātir,

in a manner that all the narrators are unanimous in reporting it with the same

words without any substantial discrepancy.

(b) Mutawātir in meaning: It is a mutawātir

hadīth which is not reported by the

narrators in the same words. The words of the narrators are different. Sometimes

even the reported events are not the same. But all the narrators are unanimous

in reporting a basic concept which is common in all the reports. This common

concept is also ranked as a mutawātir concept.

For example, there is a saying of the Holy Prophet ( ),

),

Whoever intentionally attributes a lie against me, should

prepare his seat in the Fire.

This is a mutawātir hadīth

of the first kind, because it has a minimum of seventy-four narrators. In other

words, seventy-four companions of the Holy Prophet ( )

have reported this hadīth at

different occasions, all with the same words.

)

have reported this hadīth at

different occasions, all with the same words.

The number of those who received this hadīth from these companions is many times greater, because each of

the seventy-four companions has conveyed it to a number of his pupils. Thus, the

total number of the narrators of this hadīth

has been increasing in each successive generation, and has never been less than

seventy-four. All these narrators, who are now hundreds in number, report it in

the same words without even a minor change. This hadīth is, therefore, mutawātir by words, because it cannot

be imagined reasonably that such a large number of people have colluded to coin

a fallacious sentence in order to attribute it to the Holy Prophet ( ).

).

On the other hand, it is also reported by such a large number of

narrators that the Holy Prophet ( )

has enjoined us to perform two rakāt in Fajr, four rakāt in

Zuhr, Asr and Isha, and three rakāt in the Maghrib prayer, yet

the narrations of all the reporters who reported the number of rakāt

are not in the same words. Their words are different. Even the events reported

by them are different. But the common feature of all the reports is the same.

This common feature, namely, the exact number of rakāt, is said to be

mutawātir in meaning.

)

has enjoined us to perform two rakāt in Fajr, four rakāt in

Zuhr, Asr and Isha, and three rakāt in the Maghrib prayer, yet

the narrations of all the reporters who reported the number of rakāt

are not in the same words. Their words are different. Even the events reported

by them are different. But the common feature of all the reports is the same.

This common feature, namely, the exact number of rakāt, is said to be

mutawātir in meaning.

(2) The second kind of hadīth

is Mashhoor. This term is defined by the scholars of hadīth

as follows:

A hadīth which is

not mutawātir, but its narrators are not less than three in any

generation. [Tadreeb-ur-Rāwi by Suyuti]

The same term is also used by the scholars of fiqh, but

their definition is slightly different. They say,

A mashhoor hadīth

is one which was not mutawātir in the generation of the Holy Companions,

but became mutawātir immediately after them. [Usool of

Sarkhasi]

The mashhoor hadīth

according to each definition falls in the second category following the mutawātir.

(3) Khabar-ul-Wāhid. It is a hadīth

whose narrators are less than three in any given generation.

Let us now examine each kind separately.

The Authenticity of the First Two Kinds

As for the mutawātir, nobody can question its

authenticity. The fact narrated by a mutawātir chain is always accepted

as an absolute truth even if pertaining to our daily life. Any statement based

on a mutawātir narration must be accepted by everyone without any

hesitation. I have never seen the city of Moscow, but the fact that Moscow is a

large city and is the capital of U.S.S.R. is an absolute truth which cannot be

denied. This fact is proved, to me, by a large number of narrators who have seen

the city. This is a continuously narrated, or a mutawātir, fact which

cannot be denied or questioned.

I have not seen the events of the First and the Second World

War. But the fact that these two wars occurred stands proved without a shadow of

doubt on the basis of the mutawātir reports about them. Nobody with a

sound sense can claim that all those who reported the occurrence of these two

wars have colluded to coin a fallacious report and that no war took place at

all. This strong belief in the factum of war is based on the mutawātir

reports of the event.

In the same way the mutawātir reports about the sunnah

of the Holy Prophet ( )

are to be held as absolutely true without any iota of doubt in their

authenticity. The authenticity of the Holy Qurān being the same Book as that

revealed to the Holy Prophet (

)

are to be held as absolutely true without any iota of doubt in their

authenticity. The authenticity of the Holy Qurān being the same Book as that

revealed to the Holy Prophet ( )

is of the same nature. Thus, the mutawātir ahādīth, whether they be mutawātir in words or in meaning,

are as authentic as the Holy Qurān, and there is no difference between the

two in as far as the reliability of their source of narration is concerned.

)

is of the same nature. Thus, the mutawātir ahādīth, whether they be mutawātir in words or in meaning,

are as authentic as the Holy Qurān, and there is no difference between the

two in as far as the reliability of their source of narration is concerned.

Although the ahādīth

falling under the first category of the mutawātir, ie. the mutawātir

in words, are very few in number, yet the ahādīth

relating to the second kind, namely the mutawātir in meaning, are

available in large numbers. Thus, a very sizeable portion of the sunnah

of the Holy Prophet ( )

falls in this kind of mutawātir, the authenticity of which cannot be

doubted in any manner.

)

falls in this kind of mutawātir, the authenticity of which cannot be

doubted in any manner.

As for the second kind, ie. the mashhoor, its

standard of authenticity is lower than that of the mutawātir; yet, it is

sufficient to provide satisfaction about the correctness of the narration

because its narrators have been more than three trustworthy persons in every

generation.

The third kind is khabar-ul-wāhid. The authenticity of

this kind depends on the veracity of its narrators. If the narrator is

trustworthy in all respects, the report given by him can be accepted, but if the

single reporter is believed to be doubtful, the entire report subsequently

remains doubtful. This principle is followed in every sphere of life. Why should

it not be applied to the reports about the sunnah of the Holy Prophet ( )?

Rather, in the case of ahādīth, this

principle is most applicable, because the reporters of ahādīth were fully cognizant of the delicate nature of what they

narrate. It was not simple news of an ordinary event having no legal or

religious effect. It was the narration of a fact which has a far-reaching effect

on the lives of millions of people. The reporters of ahādīth

knew well that it is not a play to ascribe a word or act to the Holy Prophet (

)?

Rather, in the case of ahādīth, this

principle is most applicable, because the reporters of ahādīth were fully cognizant of the delicate nature of what they

narrate. It was not simple news of an ordinary event having no legal or

religious effect. It was the narration of a fact which has a far-reaching effect

on the lives of millions of people. The reporters of ahādīth

knew well that it is not a play to ascribe a word or act to the Holy Prophet ( ).

Any deliberate error in this narration, or any negligence in this respect would

lead them to the wrath of Allāh and render them liable to be punished in hell.

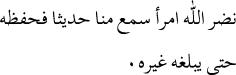

Every reporter of hadīth was aware of

the following well-known mutawātir hadīth:

).

Any deliberate error in this narration, or any negligence in this respect would

lead them to the wrath of Allāh and render them liable to be punished in hell.

Every reporter of hadīth was aware of

the following well-known mutawātir hadīth:

Whoever intentionally attributes a lie against me, should

prepare his seat in the Fire.

This hadīth had

created such a strong sense of responsibility in the hearts of the narrators of ahādīth

that while reporting anything about the Holy Prophet ( )

they often turned pale out of fear, lest some error should creep into their

narration.

)

they often turned pale out of fear, lest some error should creep into their

narration.

This was the basic reason for which the responsible narrators of

ahādīth showed the maximum

precaution in preserving and reporting a hadīth.

This standard of precaution cannot be found in any other reports of historical

events. So, the principle that the veracity of a report depends on the nature of

its reporter is far more validly applicable to the reports of ahādīth

than it is applicable to the general reports of ordinary nature.

Let us now examine the various ways adopted by the ummah

to preserve the ahādīth in their

original form.

Different Ways of Ahādīth Preservation

As we shall later see, the companions of the Holy Prophet ( )

reduced a large number of ahādīth in

writing. Yet, writing was not the sole means of their preservation. There were

many other ways.

)

reduced a large number of ahādīth in

writing. Yet, writing was not the sole means of their preservation. There were

many other ways.

1. Memorization

First of all, the companions of the Holy Prophet ( )

used to learn ahādīth by heart. The

Holy Prophet (

)

used to learn ahādīth by heart. The

Holy Prophet ( )

has said:

)

has said:

May Allāh bestow vigor to a person who hears my

saying and learns it by heart and then conveys it to others exactly as he hears

it.

The companions of the Holy Prophet ( )

were eager to follow this hadīth and

used to devote considerable time for committing ahādīth to their memories. A large number of them left their homes

and began to live in the Mosque of the Holy Prophet (

)

were eager to follow this hadīth and

used to devote considerable time for committing ahādīth to their memories. A large number of them left their homes

and began to live in the Mosque of the Holy Prophet ( )

so that they may hear the ahādīth

directly from the mouth of the Holy Prophet (

)

so that they may hear the ahādīth

directly from the mouth of the Holy Prophet ( ).

They spent all their time exclusively in securing the ahādīth in their hearts. They are called Ashāb as-Suffah.

).

They spent all their time exclusively in securing the ahādīth in their hearts. They are called Ashāb as-Suffah.

The Arabs had such strong memories that they would easily

memorize hundreds of verses of their poetry. Nearly all of them knew by heart

detailed pedigrees of not only themselves, but also of their horses and camels.

Even their children had enough knowledge of the pedigrees of different tribes.

Hammād is a famous narrator of Arab poetry. It is reported that he knew by

heart one hundred long poems for each letter of the alphabet, meaning thereby

that he knew three thousand and thirty-eight long poems [al-Alam by

Zrikli 2:131].

The Arabs were so proud of their memory power that they placed

more of their confidence on it than on writing. Some poets deemed it a blemish

to preserve their poetry in writing. They believed that writings on papers can

be tampered with, while the memory cannot be distorted by anyone. If any poets

have written some of their poems, they did not like to disclose this fact,

because it would be indicative of a defect in their memory [See al-Aghani

61:611].

The companions of the Holy Prophet ( )

utilized this memory for preserving ahādīth

which they deemed to be the only source of guidance after the Holy Qurān. It

is obvious that their enthusiasm towards the preservation of ahādīth

far exceeded their zeal for preserving their poetry and literature. They

therefore used their memory in respect of ahādīth

with more vigor and more precaution.

)

utilized this memory for preserving ahādīth

which they deemed to be the only source of guidance after the Holy Qurān. It

is obvious that their enthusiasm towards the preservation of ahādīth

far exceeded their zeal for preserving their poetry and literature. They

therefore used their memory in respect of ahādīth

with more vigor and more precaution.

Sayyidunā Abū Hurairah (

), the famous companion of the

Holy Prophet (

), the famous companion of the

Holy Prophet ( ),

who has reported 5,374 ahādīth,

says:

),

who has reported 5,374 ahādīth,

says:

I have divided my night into three parts: In one

third of the night I perform prayer, in one third I sleep and in one third I

memorize the ahādīth of the Holy Prophet ( ).

[Sunan ad-Dārimi]

).

[Sunan ad-Dārimi]

Sayyidunā Abū Hurairah (

), after embracing Islām,

devoted his life exclusively for learning the ahādīth.

He has reported more ahādīth than

any other companion of the Holy Prophet (

), after embracing Islām,

devoted his life exclusively for learning the ahādīth.

He has reported more ahādīth than

any other companion of the Holy Prophet ( ).

).

Once, Marwān, the governor of Madīnah, tried to test his

memory. He invited him to his house where he asked him to narrate some ahādīth.

Marwān simultaneously ordered his scribe, Abu Zuaiziah, to sit behind a

curtain and write the ahādīth

reported by Abū Hurairah (

).

The scribe noted the ahādīth. After

a year, he invited Abū Hurairah again and requested him to repeat what he had

narrated last year, and likewise ordered Abu Zuaiziah to sit behind a

curtain and compare the present words of Abū Hurairah (

).

The scribe noted the ahādīth. After

a year, he invited Abū Hurairah again and requested him to repeat what he had

narrated last year, and likewise ordered Abu Zuaiziah to sit behind a

curtain and compare the present words of Abū Hurairah ( )

with the ahādīth he had already

written previously. Sayyidunā Abū

Hurairah (

)

with the ahādīth he had already

written previously. Sayyidunā Abū

Hurairah (

)

began to repeat the ahādīth while

Abu Zuaiziah compared them. He found that Abū Hurairah did not leave a

single word, nor did he change any word from his earlier narrations [al-Bidāyah

wan-Nihāyah and Siyar al-Alām of Dhahabi].

)

began to repeat the ahādīth while

Abu Zuaiziah compared them. He found that Abū Hurairah did not leave a

single word, nor did he change any word from his earlier narrations [al-Bidāyah

wan-Nihāyah and Siyar al-Alām of Dhahabi].

Numerous other examples of this type are available in the

history of the science of hadīth

which clearly show that the ahādīth

reporters have used their extraordinary memory power given to them by Allāh

Almighty for preserving the Sunnah of the Holy Prophet ( ), as

promised by Him in the Holy Qurān.

), as

promised by Him in the Holy Qurān.

As we shall later see, scholars of the science of hadīth

developed the science of Asmā ur-Rijāl by which they have deduced

reliable means to test the memory power of each narrator of ahādīth.

They never accepted any hadīth as

reliable unless all of its narrators were proved to have high memory standards.

Thus, memory power in the science of hadīth is not a vague term of general nature. It is a technical

term having specified criteria to test the veracity of narrators. A great number

of scholars of the sciences of Asmā ur-Rijāl and Jarh wa Tadīl

have devoted their lives to examine the reporters of hadīth

on that criteria. Their task was to judge the memory power of each narrator and

to record objective opinions about them.

Memories of the ahādīth

reporters cannot be compared with the memory of a layman today who witnesses an

event or hears some news and conveys it to others in a careless manner seldom

paying attention to the correctness of his narration. The following points in

this respect are worth mentioning:

1. The reporters of ahādīth

were fully cognizant of the great importance and the delicate nature of what

they intended to report. They whole-heartedly believed that any misstatement or

negligent reporting in this field would cause them to be condemned both in this

world and in the Hereafter. This belief equipped them with a very strong sense

of responsibility. It is evident that such a strong sense of responsibility

makes a reporter more accurate in his reports. A newsman reporting an accident

of a common nature in which common people are involved, can report its details

with less accuracy. But if the accident involves the President or the Prime

Minister of his country, he will certainly show more diligence, precaution and

shall employ his best ability to report the incident as accurately as possible.

The reporter is the same, but in the second case he is more accurate in his

report than he was in the first case, because the nature of the incident has

made him more responsible, hence more cautious.

It cannot be denied that the companions of the Holy Prophet ( ), their

pupils, and other reliable narrators of ahādīth believed with their heart and soul that the importance of

a hadīth attributed to the Holy

Prophet (

), their

pupils, and other reliable narrators of ahādīth believed with their heart and soul that the importance of

a hadīth attributed to the Holy

Prophet ( )

exceeds the importance of any other report whatsoever. They believed that it is

a source of Islāmic law which will govern the Ummah for all times to come. They

believed that any negligence in this respect will lead them to the severe

punishment of hell. So, their sense of responsibility while reporting ahādīth

was far higher than that of a newsman reporting an important incident about the

head of his country.

)

exceeds the importance of any other report whatsoever. They believed that it is

a source of Islāmic law which will govern the Ummah for all times to come. They

believed that any negligence in this respect will lead them to the severe

punishment of hell. So, their sense of responsibility while reporting ahādīth

was far higher than that of a newsman reporting an important incident about the

head of his country.

2. The interest of the reporter in the reported events and his

ability to understand them correctly is another important factor which affects

the accuracy of his report. If the reporter is indifferent or negligent about

what he reports, little reliability can be placed on his memory or on any

subsequent report based on it. But if the reporter is not only honest, serious,

and intelligent but also interested and involved in the event, his report can

easily be relied upon.

If some proceedings are going on in a court of law, the reports

of these proceedings can be of different kinds. One report was given by a layman

from the audience who was incidentally present at the court. He had neither any

interest in the proceedings nor had due knowledge and understanding of the legal

issues involved. He gathered a sketchy picture of the proceedings and reported

it to a third person. Such a report can neither be relied upon nor taken as an

authentic version of the proceedings. This report may be full of errors because

the reporter lacks the ability to understand the matter correctly and the

responsible attitude to report it accurately. Such a reporter may not only err

in his reporting, but may after some time also forget the proceedings

altogether.

Suppose there are some newsmen also who have witnessed the

proceedings for the purpose of reporting them in their newspapers. They have

more knowledge and understanding than a layman of the first kind. Their report

shall be more correct than that of the former. But despite their interest and

intelligence, they are not fully aware of the technical and legal questions

involved in the proceedings. Their report shall thus remain deficient in the

legal aspect of the proceedings and cannot be relied upon to that extent because

despite their good memory, they cannot grasp the legal issues completely.

There were also lawyers who were directly involved in the

proceedings. They participated in the debate at the bar. They have argued the

case. They were fully aware of the delicate legal issues involved. They

understood each and every sentence expressed by other lawyers and the judge. It

is obvious that the report of the proceedings given by these lawyers shall be

the most authentic one. Having full knowledge and understanding of the case they

can neither forget nor err while reporting the substantial and material parts of

the proceedings.

Suppose all the three categories had the same standard of memory

power. Yet, the facts narrated by them have different levels of correctness. It

shows that the interest of the reporter in the reported event and his

understanding of the facts involved plays an important role in making his memory

more effective and accurate.

The deep interest of the companions of the Holy Prophet ( ) in his

sayings and acts, rather even in his gestures, is beyond any doubt. Their

understanding of what he said, and their close knowledge and observation of the

background and the environment under which he spoke or acted cannot be

questioned. Thus, all the basic factors which help mobilize ones memory were

present in them.

) in his

sayings and acts, rather even in his gestures, is beyond any doubt. Their

understanding of what he said, and their close knowledge and observation of the

background and the environment under which he spoke or acted cannot be

questioned. Thus, all the basic factors which help mobilize ones memory were

present in them.

3. The standard of memory power required for the authenticity of

a report is not, as mentioned earlier, a vague concept for which no specific

criteria exist. The scholars of the Science of hadīth have laid down hard and fast rules to ascertain the memory

standard of each reporter. Unless a reporter of a hadīth has specific standards of memory, his reports and not

accepted as reliable.

4. There is a big difference between memorizing a fact which

incidentally came to the knowledge of someone who never cared to remember it any

more, and the memorizing of a fact which is learnt by someone with eagerness,

with an objective purpose to remember it and with a constant effort to keep it

in memory.

While I studied Arabic, my teacher told me many things which I

do not remember today. But the vocabulary I learnt from my teacher is secured in

my mind. The reason is obvious. I never cared to keep the former remembered,

while I was very much eager to learn the latter by heart and to store it in my

memory.

The companions of the Holy Prophet ( ) did

not listen to him incidentally nor were they careless in remembering what they

heard. Instead, they daily spared specific times for learning the ahādīth

by heart. The example of Abū Hurairah has already been cited. He used to spare

one third of every night in repeating the ahādīth

he learnt from the Holy Prophet (

) did

not listen to him incidentally nor were they careless in remembering what they

heard. Instead, they daily spared specific times for learning the ahādīth

by heart. The example of Abū Hurairah has already been cited. He used to spare

one third of every night in repeating the ahādīth

he learnt from the Holy Prophet ( ).

).

Thus, memorization was not a weaker source of preservation of ahādīth,

as is sometimes presumed by those who have no proper knowledge of the science of

hadīth. Looked at in its true perspective, the memories of the

reliable reporters of ahādīth were

no less reliable a source of preservation than compiling the ahādīth in book form.

2. Discussions

The second source of preservation of ahādīth was by mutual discussions held by the companions of the

Holy Prophet ( ).

Whenever they came to know of a new sunnah, they used to narrate it to

others. Thus, all the companions would tell each other what they learnt from the

Holy Prophet (

).

Whenever they came to know of a new sunnah, they used to narrate it to

others. Thus, all the companions would tell each other what they learnt from the

Holy Prophet ( ). This

was to comply with the specific directions given by the Holy Prophet (

). This

was to comply with the specific directions given by the Holy Prophet ( ) in

this respect. Here are some ahādīth

to this effect:

) in

this respect. Here are some ahādīth

to this effect:

Those present should convey (my sunnah)

to those absent [Bukhari].

Convey to others on my behalf, even though it be a single verse

[Bukhari].

May Allāh grant vigor to a person who listens to my saying and

learns it by heart until he conveys it to others [Tirmidhi,

Abu Dāwūd].

You hear (my sayings) and others will hear from you, then

others will hear from them [Abu Dāwūd].

A Muslim cannot offer his brother a better benefit than

transmitting to him a good hadīth which has reached him [Jāmi-ul-Bayān of Ibn Abdul Barr].

These directions given by the Holy Prophet ( ) were

more than sufficient to induce his companions towards acquiring the knowledge of

ahādīth and to convey them to

others.

) were

more than sufficient to induce his companions towards acquiring the knowledge of

ahādīth and to convey them to

others.

The Holy Prophet ( ) also

motivated his companions to study the ahādīth

in their meetings. The word used for this study is Tadarus which means

to teach each other. One person would narrate a particular hadīth

to the other who, in turn, would repeat it to the first, and so on. The purpose

was to learn it correctly. Each one would listen to the others version and

correct his mistake, if any. The result of this tadarus (discussion) was

to remember the ahādīth as firmly as

possible. The Holy Prophet (

) also

motivated his companions to study the ahādīth

in their meetings. The word used for this study is Tadarus which means

to teach each other. One person would narrate a particular hadīth

to the other who, in turn, would repeat it to the first, and so on. The purpose

was to learn it correctly. Each one would listen to the others version and

correct his mistake, if any. The result of this tadarus (discussion) was

to remember the ahādīth as firmly as

possible. The Holy Prophet ( ) has

held this described process of tadarus to be more meritorious with Allāh

than the individual worship throughout the night. He has said:

) has

held this described process of tadarus to be more meritorious with Allāh

than the individual worship throughout the night. He has said:

Tadarus of knowledge

(the word knowledge in the era of Nabī ( ) was

used to connote knowledge relative to the Holy Qurān and the hadīth) for

any period of time in the night is better than spending the entire night in

worship [Jāmi-ul-Bayān].

) was

used to connote knowledge relative to the Holy Qurān and the hadīth) for

any period of time in the night is better than spending the entire night in

worship [Jāmi-ul-Bayān].

Moreover, the Holy Prophet ( ) has

also warned, that it is a major sin to hide a word of knowledge whenever

it is asked for:

) has

also warned, that it is a major sin to hide a word of knowledge whenever

it is asked for:

Whoever is questioned pertaining to such knowledge that he has

and thereafter conceals it, will be bridled by a rein of fire [Tirmidhi].

At another occasion, the Holy Prophet ( )

disclosed that concealment of knowledge is in itself a major sin, even

though the person having that knowledge is not asked about it. He said:

)

disclosed that concealment of knowledge is in itself a major sin, even

though the person having that knowledge is not asked about it. He said:

Whoever conceals knowledge which can be benefited from, will

come on Doomsday bridled with a bridle of fire [Jāmi-ul-Bayān].

The hadīth makes it

clear that the disclosure of knowledge is an inherent obligation on each

knowledgeable person, no matter whether he is asked about it or not.

As the knowledge of the sunnah of the Holy Prophet ( ) was

the highest branch of knowledge in the eyes of his companions, they deemed it an

indispensable obligation on their shoulders to convey to others what they knew

of the sunnah.

) was

the highest branch of knowledge in the eyes of his companions, they deemed it an

indispensable obligation on their shoulders to convey to others what they knew

of the sunnah.

Thus, it was the most favorite hobby of the companions of the

Holy Prophet ( )

whenever they sat together, instead of being involved in useless talks, to

discuss his sayings and acts. Each of them would mention what he knew while the

others would listen and try to learn it by heart.

)

whenever they sat together, instead of being involved in useless talks, to

discuss his sayings and acts. Each of them would mention what he knew while the

others would listen and try to learn it by heart.

These frequent discussions have played an important role in the

preservation of the Sunnah. It was by the virtue of these discussions

that the ahādīth known only by some

individuals were conveyed to others, and the circle of narrators was gradually

enlarged. Since these discussions were carried out at a time when the Holy

Prophet ( ) was

himself present among them, they had the full opportunity to confirm the

veracity of what has been conveyed to them in this process, and some of them

actually did so. The result was that the knowledge of ahādīth acquired a wide range among the companions, which not only

helped in spreading the knowledge of Sunnah but also provided a check on

the mistakes of narrations, because if someone forgets some part of a hadīth,

the others were present to fill in the gap and to correct the error.

) was

himself present among them, they had the full opportunity to confirm the

veracity of what has been conveyed to them in this process, and some of them

actually did so. The result was that the knowledge of ahādīth acquired a wide range among the companions, which not only

helped in spreading the knowledge of Sunnah but also provided a check on

the mistakes of narrations, because if someone forgets some part of a hadīth,

the others were present to fill in the gap and to correct the error.

3. Practice

The third way of preservation of the Sunnah was to bring

it into practice.

The knowledge of Sunnah was not merely a theoretical

knowledge, nor were the teachings of the Holy Prophet ( ) merely

philosophical. They related to practical life. The Holy Prophet (

) merely

philosophical. They related to practical life. The Holy Prophet ( ) did

not confine himself to giving lessons and sermons only, he also trained his

companions practically. Whatever they learnt from the Holy Prophet (

) did

not confine himself to giving lessons and sermons only, he also trained his

companions practically. Whatever they learnt from the Holy Prophet ( ) they

spared no effort to bring it into actual practice. Each companion was so

enthusiastic in practicing the Sunnah of the Holy Prophet (

) they

spared no effort to bring it into actual practice. Each companion was so

enthusiastic in practicing the Sunnah of the Holy Prophet ( ) that

he tried his best to imitate even his personal habits.

) that

he tried his best to imitate even his personal habits.

Thus the whole atmosphere was one of following the Sunnah.

The Sunnah was not a verbal report only, it was a living practice, a

widespread behavior and a current fashion demonstrating itself everywhere in the

society, in all the affairs of their daily life.

If a student of mathematics confines himself with remembering

the formulas orally, he is likely to forget them after a lapse of time, but if

he brings them in practice, ten times a day, he shall never forget them.

Likewise, the Sunnah was not an oral service carried out

by the companions. They brought it into their daily practice. The Sunnah was the center of gravity for all their activities. How could they

forget the Sunnah

of the Holy Prophet ( ) around

which they built the structure of their whole lives?

) around

which they built the structure of their whole lives?

Thus, constant practice in accordance with the dictates of the Sunnah

was another major factor which advanced the process of preserving the Sunnah

and protected it from the foreign elements aiming at its distortion.

4. Writing

The fourth way of preserving of ahādīth was writing.

Quite a large number of the companions of the Holy Prophet ( )

reduced the ahādīth to writing after

hearing them from the Holy Prophet (

)

reduced the ahādīth to writing after

hearing them from the Holy Prophet ( ).

).

It is true that in the beginning the Holy Prophet ( ) had

forbidden some of his companions from writing anything other than the verses of

the Holy Qurān. However, this prohibition was not because the ahādīth

had no authoritative value, but because the Holy Prophet (

) had

forbidden some of his companions from writing anything other than the verses of

the Holy Qurān. However, this prohibition was not because the ahādīth

had no authoritative value, but because the Holy Prophet ( ) had in

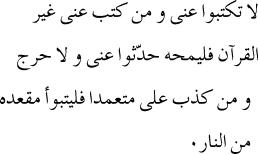

the same breath ordered them to narrate his ahādīth orally. The full text of the relevant hadīth is as follows:

) had in

the same breath ordered them to narrate his ahādīth orally. The full text of the relevant hadīth is as follows:

Do not write (what you hear) from me, and whoever has written

something (he heard) from me, he should erase it. Narrate to others (what you

hear) from me; and whoever deliberately attributes a lie to me, he should

prepare his seat in the Fire. [Sahih Muslim]

The underlined phrase of the hadīth

clarifies that prohibition for writing hadīth

was not on account of negating its authority. The actual reason was that in the

beginning of the revelation of the Holy Qurān, the companions of the Holy

Prophet ( ) were

not fully familiar with the Qurānic style, nor was the Holy Qurān

compiled in a separate book form. In those days some companions began to write

the ahādīth along with the Qurānic

text. Some explanations of the Holy Qurān given by the Holy Prophet (

) were

not fully familiar with the Qurānic style, nor was the Holy Qurān

compiled in a separate book form. In those days some companions began to write

the ahādīth along with the Qurānic

text. Some explanations of the Holy Qurān given by the Holy Prophet ( ) were

written by some of them mixed with the Qurānic verses without any

distinction between the two. It was therefore feared that it would lead to

confuse the Qurānic text with the ahādīth.

) were

written by some of them mixed with the Qurānic verses without any

distinction between the two. It was therefore feared that it would lead to

confuse the Qurānic text with the ahādīth.

It was in this background that the Holy Prophet ( )

stopped this practice and ordered that anything written other than the Holy

Qurān should be rubbed or omitted. It should be kept in mind that in those

days there was a great shortage of writing paper. Even the verses of the Holy

Qurān used to be written on pieces of leather, on planks of wood, on animal

bones and sometimes on stones. It was much difficult to compile all those things

in a book form, and if the ahādīth

were also written in the like manner it would be more difficult to distinguish

between the writings of the Holy Qurān and those of the ahādīth. The lack of familiarity with the Qurānic style would

also help creating confusion.

)

stopped this practice and ordered that anything written other than the Holy

Qurān should be rubbed or omitted. It should be kept in mind that in those

days there was a great shortage of writing paper. Even the verses of the Holy

Qurān used to be written on pieces of leather, on planks of wood, on animal

bones and sometimes on stones. It was much difficult to compile all those things

in a book form, and if the ahādīth

were also written in the like manner it would be more difficult to distinguish

between the writings of the Holy Qurān and those of the ahādīth. The lack of familiarity with the Qurānic style would

also help creating confusion.

For these reasons the Holy Prophet ( )

directed his companions to abstain from writing the ahādīth and to confine their preservation to the first three ways

which were equally reliable as discussed earlier.

)

directed his companions to abstain from writing the ahādīth and to confine their preservation to the first three ways

which were equally reliable as discussed earlier.

But all this was in the earlier period of his prophethood. When

the companions became fully conversant of the style of the Holy Qurān and

writing paper became available, this transitory measure of precaution was taken

back, because the danger of confusion between the Qurān and the hadīth

no longer existed.

At this stage, the Holy Prophet ( )

himself directed his companions to write down the ahādīth. Some of his instructions in this respect are quoted

below:

)

himself directed his companions to write down the ahādīth. Some of his instructions in this respect are quoted

below:

1. One companion from the Ansār complained to the Holy

Prophet ( ) that

he hears from him some ahādīth, but

he sometimes forgets them. The Holy Prophet (

) that

he hears from him some ahādīth, but

he sometimes forgets them. The Holy Prophet ( ) said:

) said:

Seek help from your right hand, and pointed out to a

writing. [Jāmi Tirmidhi]

2. Rāfi ibn Khadij (

), the famous companion of the

Holy Prophet (

), the famous companion of the

Holy Prophet ( ) says,

I said to the Holy Prophet (

) says,

I said to the Holy Prophet ( ) [that]

we hear from you many things, should we write them down? He replied:

) [that]

we hear from you many things, should we write them down? He replied:

You may write. There is no harm.

[Tadrīb-ur-Rāwi]

3. Sayyiduna Anas (

)

reports that the Holy Prophet (

)

reports that the Holy Prophet ( ) has

said:

) has

said:

Preserve knowledge by writing.

[Jāmi-ul-Bayān]

4. Sayyiduna Abu Rāfi (

) sought permission from the

Holy Prophet (

) sought permission from the

Holy Prophet ( ) to

write ahādīth. The Holy Prophet (

) to

write ahādīth. The Holy Prophet ( )

permitted him to do so. [Jāmi Tirmidhi]

)

permitted him to do so. [Jāmi Tirmidhi]

It is reported that the ahādīth

written by Abu Rāfi (

) were copied by other

companions too. Salma, a pupil of Ibn Abbās (

) were copied by other

companions too. Salma, a pupil of Ibn Abbās (

) says:

) says:

I saw some small wooden boards with Abdullāh Ibn Abbās.

He was writing on them some reports of the acts of the Holy Prophet ( ) which

he acquired from Abu Rāfi. [Tabaqāt Ibn

Sad]

) which

he acquired from Abu Rāfi. [Tabaqāt Ibn

Sad]

5. Abdullāh ibn Amr ibn al-Ās ( )

reports that the Holy Prophet (

)

reports that the Holy Prophet ( ) said

to him:

) said

to him:

Preserve knowledge.

He asked, and how should it be preserved? The Holy Prophet

( )

replied, by writing it. [Mustadrik Hākim; Jāmi-ul-Bayān]

)

replied, by writing it. [Mustadrik Hākim; Jāmi-ul-Bayān]

In another report he says, I came to the Holy Prophet ( ) and

told him, I want to narrate your ahādīth.

So, I want to take assistance of my handwriting besides my heart. Do you deem it

fit for me? The Holy Prophet (

) and

told him, I want to narrate your ahādīth.

So, I want to take assistance of my handwriting besides my heart. Do you deem it

fit for me? The Holy Prophet ( )

replied, If it is my hadīth you

may seek help from your hand besides your heart. [Sunan Dārimi]

)

replied, If it is my hadīth you

may seek help from your hand besides your heart. [Sunan Dārimi]

6. It was for this reason that he used to write ahādīth

frequently. He himself says,

I used to write whatever I heard from the Holy Prophet ( )

and wanted to learn it by heart. Some people of the Quraysh dissuaded me and

said, Do you write everything you hear from the Holy Prophet (

)

and wanted to learn it by heart. Some people of the Quraysh dissuaded me and

said, Do you write everything you hear from the Holy Prophet ( ),

while he is a human being and sometimes he may be in anger as any other human

beings may be? [Sunan Abu Dāwūd]

),

while he is a human being and sometimes he may be in anger as any other human

beings may be? [Sunan Abu Dāwūd]

They meant that the Holy Prophet ( )

might say something in a state of anger which he did not seriously intend. So,

one should be selective in writing his ahādīth.

Abdullāh ibn Amr conveyed their opinion to the Holy Prophet (

)

might say something in a state of anger which he did not seriously intend. So,

one should be selective in writing his ahādīth.

Abdullāh ibn Amr conveyed their opinion to the Holy Prophet ( ). In

reply, the Holy Prophet (

). In

reply, the Holy Prophet ( )

pointed to his lips and said,

)

pointed to his lips and said,

I swear by the One in whose hands is the soul of Muhammad:

nothing comes out from these two (lips) except truth. So, do write.

[Sunan Abu Dāwud; Tabaqāt ibn Sad; Mustadrik-ul-Hākim]

It was a clear and absolute order given by the Holy Prophet ( ) to

write each and every saying of his without any hesitation or doubt about its

authoritative nature.

) to

write each and every saying of his without any hesitation or doubt about its

authoritative nature.

In compliance to this order, Abdullāh ibn Amr wrote a

large number of ahādīth and compiled

them in a book form which he named, al-Sahīfah al-Sadīqah. Some

details about this book shall be discussed later on, inshā-Allāh.

7. During the conquest of Makkah (8 A.H.), the Holy Prophet ( )

delivered a detailed sermon containing a number of Sharīah imperatives,

including human rights. One Yemenite person from the gathering, namely, Abu

Shah, requested the Holy Prophet (

)

delivered a detailed sermon containing a number of Sharīah imperatives,

including human rights. One Yemenite person from the gathering, namely, Abu

Shah, requested the Holy Prophet ( ) to

provide him the sermon in a written form. The Holy Prophet (

) to

provide him the sermon in a written form. The Holy Prophet ( )

thereafter ordered his companions as follows:

)

thereafter ordered his companions as follows:

Write it down for Abu Shah. [Sahīh-ul-Bukhāri]

These seven examples are more than sufficient to prove that the

writing of ahādīth was not only

permitted but also ordered by the Holy Prophet ( ) and

that the earlier bar against writing was only for a transitory period to avoid

any possible confusion between the verses of the Holy Qurān and the ahādīth.

After this transitory period the fear of confusion ended, the bar was lifted and

the companions were persuaded to preserve ahādīth

in a written form.

) and

that the earlier bar against writing was only for a transitory period to avoid

any possible confusion between the verses of the Holy Qurān and the ahādīth.

After this transitory period the fear of confusion ended, the bar was lifted and

the companions were persuaded to preserve ahādīth

in a written form.

The Compilation of Hadīth in the

Days of the Holy Prophet ( )

)

We have discussed the different methods undertaken by the

companions of the Holy Prophet ( ) to preserve the ahādīth.

An objective study of these methods would prove that although writing was

not the sole method of their preservation, yet it was never neglected in this

process. Inspired by the Holy Prophet (

) to preserve the ahādīth.

An objective study of these methods would prove that although writing was

not the sole method of their preservation, yet it was never neglected in this

process. Inspired by the Holy Prophet ( ) himself, a large number of

his companions used to secure the ahādīth

in written form.

) himself, a large number of

his companions used to secure the ahādīth

in written form.

When we study individual efforts of the companions for compiling

ahādīth, we find that thousands of ahādīth

were written in the very days of the Holy Prophet ( ) and his four Caliphs. It is

not possible to give an exhaustive survey of these efforts, for it will require

a separate voluminous book on the subject which is not intended here.

Nevertheless, we propose to give a brief account of some outstanding

compilations of ahādīth in that

early period. It will, at least, refute the misconception that the ahādīth

were not compiled during the first three centuries.

) and his four Caliphs. It is

not possible to give an exhaustive survey of these efforts, for it will require

a separate voluminous book on the subject which is not intended here.

Nevertheless, we propose to give a brief account of some outstanding

compilations of ahādīth in that

early period. It will, at least, refute the misconception that the ahādīth

were not compiled during the first three centuries.

The Dictations of the Holy Prophet ( )

)

To begin with, we would refer to the fact that a considerable

number of ahādīth were dictated and

directed to be secured in written form by the Holy Prophet ( ) himself. Here are some

examples:

) himself. Here are some

examples:

The Book of Sadaqah

The Holy Prophet ( ) has dictated detailed

documents containing rules of Sharīah about the levy of Zakāh,

and specifying the quantum and the rate of Zakāh in respect of different

Zakāt-able assets. This document was named Kitāb as-Sadaqah

(The Book of Sadaqah). Abdullāh ibn Umar (

) has dictated detailed

documents containing rules of Sharīah about the levy of Zakāh,

and specifying the quantum and the rate of Zakāh in respect of different

Zakāt-able assets. This document was named Kitāb as-Sadaqah

(The Book of Sadaqah). Abdullāh ibn Umar ( )

says,

)

says,

The Holy Prophet ( ) dictated the Book of Sadaqah

and was yet to send it to his governors when he passed away. He had attached it

to his sword. When he passed away, Abu Bakr acted according to it till he passed

away, then Umar acted according to it till he passed away. It was mentioned

in his book that one goat is leviable on five camels

[Jāmi Tirmidhi]

) dictated the Book of Sadaqah

and was yet to send it to his governors when he passed away. He had attached it

to his sword. When he passed away, Abu Bakr acted according to it till he passed

away, then Umar acted according to it till he passed away. It was mentioned

in his book that one goat is leviable on five camels

[Jāmi Tirmidhi]

The text of this document is available in several books of ahādīth

like the Sunan of Abu Dāwūd. Imām Zuhri, the renowned scholar of hadīth,

used to teach this document to his pupils. He used to say:

This is the text of the document dictated by the Holy Prophet ( ) about the rules of Sadaqah (Zakāh).

Its original manuscript is with the children of Sayyiduna Umar. Salim, the

grandson of Umar had taught it to me. I had learnt it by heart. Umar ibn

Abdul-Azīz had procured a copy of this text from Salim and Abdullah, the

grandsons of Umar. I have the same copy with me.

[Sunan Abu Dāwūd]

) about the rules of Sadaqah (Zakāh).

Its original manuscript is with the children of Sayyiduna Umar. Salim, the

grandson of Umar had taught it to me. I had learnt it by heart. Umar ibn

Abdul-Azīz had procured a copy of this text from Salim and Abdullah, the

grandsons of Umar. I have the same copy with me.

[Sunan Abu Dāwūd]

The Script of Amr ibn Hazm

In 10 A.H., when Najran was conquered by the Muslims, the Holy

Prophet ( ) appointed his companion,

Amr ibn Hazm (

) appointed his companion,

Amr ibn Hazm (

), as governer of

the province of Yemen. At this time the Holy Prophet (

), as governer of

the province of Yemen. At this time the Holy Prophet ( ) dictated a detailed book to

Ubayy ibn Kab (

) dictated a detailed book to

Ubayy ibn Kab (

) and

handed it over to Amr ibn Hazm.

) and

handed it over to Amr ibn Hazm.

This book, besides some general advices, contained the rules of Sharīah

about purification, salāh, zakāh, ushr, hajj, umrah,

jihād (battle), spoils, taxes, diyah (blood money),

administration, education, etc.

Sayyiduna Amr ibn Hazm performed his functions as governor of

Yemen in the light of this book. After his demise this document remained with

his grandson, Abu Bakr. Imām Zuhri learnt and copied it from him. He used to

teach it to his pupils. [Certain extracts of this book are found in the works of

hadīth. For the full text see, al-Wathāiq

as-Sayāsiyyah fil-Islām by Dr. Hamīdullāh.]

Written Directives to Other Governors

Similarly, when the Holy Prophet ( ) appointed some of his

companions as governors of different provinces he used to dictate to them

similar documents as his directives which they could follow in performing their

duties as rulers or as judges. When he appointed Abu Hurairah and Ala ibn al-Hazrami

as his envoy to the Zoroastrians of Hajar, he dictated to them a directive

containing certain rules of Sharīah about Zakāh and Ushr.

[Tabaqāt Ibn Sad]

) appointed some of his

companions as governors of different provinces he used to dictate to them

similar documents as his directives which they could follow in performing their

duties as rulers or as judges. When he appointed Abu Hurairah and Ala ibn al-Hazrami

as his envoy to the Zoroastrians of Hajar, he dictated to them a directive

containing certain rules of Sharīah about Zakāh and Ushr.

[Tabaqāt Ibn Sad]

Likewise, when he sent Muādh ibn Jabal and Malik ibn Murarah

to Yemen, he gave them a document dictated by him which contained certain rules

of Sharīah. [ibid]

Written Directives for Certain Delegations

Certain Arab tribes who lived in remote areas far from Madīnah,

after embracing Islām used to send their delegations to the Holy Prophet ( ). These delegations used to

stay at Madīnah for a considerable period during which they would learn the

teachings of Islām, read the Holy Qurān and listen to the sayings of the

Holy Prophet (

). These delegations used to

stay at Madīnah for a considerable period during which they would learn the

teachings of Islām, read the Holy Qurān and listen to the sayings of the

Holy Prophet ( ). When they returned to their

homes, some of them requested the Holy Prophet (

). When they returned to their

homes, some of them requested the Holy Prophet ( ) to dictate some instructions

for them and for their tribes. The Holy Prophet (

) to dictate some instructions

for them and for their tribes. The Holy Prophet ( ) used to accept this request

and would dictate some directives containing such rules of Sharīah as

they most needed.

) used to accept this request

and would dictate some directives containing such rules of Sharīah as

they most needed.

1. Sayyiduna Wail ibn Hujr (

) came

from Yemen and before leaving for home, requested the Holy Prophet (

) came

from Yemen and before leaving for home, requested the Holy Prophet ( ):

):

Write me a book addressed to my tribe.

The Holy Prophet ( ) dictated three documents to

Sayyiduna Muawiyah (

) dictated three documents to

Sayyiduna Muawiyah ( ).

One of these documents pertained to personal problems of Wail ibn Hujr, while

the other two consisted of certain general precepts of Sharīah

concerning Salāh, Zakāh, prohibition of liquor, usury, and certain

other matters. [ibid]

).

One of these documents pertained to personal problems of Wail ibn Hujr, while

the other two consisted of certain general precepts of Sharīah

concerning Salāh, Zakāh, prohibition of liquor, usury, and certain

other matters. [ibid]

2. Munqiz ibn Hayyan (

), a

member of the tribe of Abdul-Qais, came to the Holy Prophet (

), a

member of the tribe of Abdul-Qais, came to the Holy Prophet ( ) and embraced Islām. While

returning home he was given a written document by the Holy Prophet (

) and embraced Islām. While

returning home he was given a written document by the Holy Prophet ( ) which he carried to his tribe

but initially he did not disclose it to anyone. When, due to his efforts, his

father-in-law embraced Islām, he handed over the document to him who in turn

read it before his tribe which subsequently embraced Islām. It was after this

that the famous delegation of Abdul-Qais came to the Holy Prophet (

) which he carried to his tribe

but initially he did not disclose it to anyone. When, due to his efforts, his

father-in-law embraced Islām, he handed over the document to him who in turn

read it before his tribe which subsequently embraced Islām. It was after this

that the famous delegation of Abdul-Qais came to the Holy Prophet ( ). The detailed narration is

found in the books of Bukhāri and Muslim. [Mirqāt Sharh Mishkāt; Sharh an-Nawawi]

). The detailed narration is

found in the books of Bukhāri and Muslim. [Mirqāt Sharh Mishkāt; Sharh an-Nawawi]

3. The delegation of the tribe of Ghamid came to the Holy

Prophet ( ) and embraced Islām. The Holy

Prophet (

) and embraced Islām. The Holy

Prophet ( ) sent them to Sayyiduna Ubayy

ibn Kab who taught them the Holy Qurān and:

) sent them to Sayyiduna Ubayy

ibn Kab who taught them the Holy Qurān and:

the Holy Prophet ( ) dictated for them a book

containing injunctions of Islām. [Tabaqāt

Ibn Sad]

) dictated for them a book

containing injunctions of Islām. [Tabaqāt

Ibn Sad]

4. The delegation of the tribe of Khatham came to the Holy

Prophet ( ). While discussing their

arrival Ibn Sad reports on the authority of different reliable narrators:

). While discussing their

arrival Ibn Sad reports on the authority of different reliable narrators:

They said, We believe in Allāh, His

messenger and in whatever has come from Allāh. So, write for us a document that

we may follow. The Holy Prophet ( ) wrote for them a document.

Jarir ibn Abdullāh and those present stood as witnesses to that document.

[ibid]

) wrote for them a document.

Jarir ibn Abdullāh and those present stood as witnesses to that document.

[ibid]

5. The delegation of the tribes of Sumalah and Huddan came after

the conquest of Makkah. They embraced Islām. The Holy Prophet ( ) dictated for them a document

containing Islāmic injunctions about Zakāh. Sayyiduna Thābit ibn Qais had written the document and Sad ibn Ubādah

and Muhammad ibn Maslamah stood as witnesses. [ibid]

) dictated for them a document

containing Islāmic injunctions about Zakāh. Sayyiduna Thābit ibn Qais had written the document and Sad ibn Ubādah

and Muhammad ibn Maslamah stood as witnesses. [ibid]

6. The same Thābit ibn

Qais ( )

also wrote a document dictated by the Holy Prophet (

)

also wrote a document dictated by the Holy Prophet ( ) for the delegation of the

tribe of Aslam. The witnesses were Abu Ubaidah ibn al-Jarrah and Umar ibn al-Khattāb.

) for the delegation of the

tribe of Aslam. The witnesses were Abu Ubaidah ibn al-Jarrah and Umar ibn al-Khattāb.

These are only a few examples which are neither comprehensive

nor exhaustive. Many other instances of the same nature are found in only one

book, namely the Tabaqāt of Ibn Sad. A thorough research in all the

relevant books would certainly expose a large number of like events for which a

more detailed book is required.

All these examples refer to those events only where the Holy

Prophet ( ) dictated documents containing

general Islāmic injunctions. He has also dictated numerous official documents

in individual cases. The large number of such documents prevents us from

providing even a short reference to all of them in this brief study. All these

documents also form part of the Sunnah and a large number of Islāmic

injunctions are inferred from them. In brevity, we instead would only refer to a

work of Dr. Muhammad Hamīdullāh, namely, al-Wathāiq as-Siyāsiyyah,

in which he has compiled a considerable number of such documents. Those who

desire further study may peruse the same.

) dictated documents containing

general Islāmic injunctions. He has also dictated numerous official documents

in individual cases. The large number of such documents prevents us from

providing even a short reference to all of them in this brief study. All these

documents also form part of the Sunnah and a large number of Islāmic

injunctions are inferred from them. In brevity, we instead would only refer to a

work of Dr. Muhammad Hamīdullāh, namely, al-Wathāiq as-Siyāsiyyah,

in which he has compiled a considerable number of such documents. Those who

desire further study may peruse the same.

The Compilations of Hadīth by the

Companions of the Holy Prophet ( )

)

As discussed earlier, the Holy Prophet ( ) has not only permitted but

also persuaded his companions to write down his ahādīth.

In pursuance of this direction, the blessed companions of the Holy Prophet (

) has not only permitted but

also persuaded his companions to write down his ahādīth.

In pursuance of this direction, the blessed companions of the Holy Prophet ( ) used to write ahādīth,

and a considerable number of them have compiled these writings in book forms.

Some examples are given below.

) used to write ahādīth,

and a considerable number of them have compiled these writings in book forms.

Some examples are given below.

The Scripts of Abu Hurairah ( )

)

It is well-known that Abu Hurairah ( )

has narrated more ahādīth than any

other companion of the Holy Prophet (

)

has narrated more ahādīth than any

other companion of the Holy Prophet ( ). The number of ahādīth

reported by him is said to be 5374. The reason was that he, after embracing Islām,

devoted his full life for the sole purpose of bearing and preserving the ahādīth

of the Holy Prophet (

). The number of ahādīth

reported by him is said to be 5374. The reason was that he, after embracing Islām,

devoted his full life for the sole purpose of bearing and preserving the ahādīth

of the Holy Prophet ( ). Unlike the other famous

companions, he did not employ himself in any economic activity. He used to

remain in the mosque of the Holy Prophet (

). Unlike the other famous

companions, he did not employ himself in any economic activity. He used to

remain in the mosque of the Holy Prophet ( ) to hear what he said and to

witness each event around him. He remained hungry, faced starvations and

hardships. Yet, he did not leave the function he had undertaken.

) to hear what he said and to

witness each event around him. He remained hungry, faced starvations and

hardships. Yet, he did not leave the function he had undertaken.

There are concrete evidences that he had preserved the ahādīth

in written form. One of his pupils, namely, Hasan ibn Amr reports that once:

Abu Hurairah (

) took

him to his home and showed him many books containing the ahādīth

of the Holy Prophet (

) took

him to his home and showed him many books containing the ahādīth

of the Holy Prophet ( ). [Jāmi Bayān-ul-Ilm;

Fath-ul-Bāri]

). [Jāmi Bayān-ul-Ilm;

Fath-ul-Bāri]

It shows that Abu Hurairah had many scripts of ahādīth

with him. It is also established that a number of his pupils had prepared

several scripts of his narrations.

The Script of Abdullāhi ibn Amr ( )

)

It has been stated earlier that Abdullāh ibn Amr was

specifically instructed by the Holy Prophet ( ) to write ahādīth.

He therefore compiled a big script and named it As-Sahīfah as-Sādiqah

(The script of truth). Abdullāh ibn Amr was very precautious in

preserving this script. Mujāhid, one of his favorite pupils says, I went to

Abdullāh ibn Amr and took in hand a script placed beneath his cushion. He

stopped me. I said, You never save anything from me. He replied:

) to write ahādīth.

He therefore compiled a big script and named it As-Sahīfah as-Sādiqah

(The script of truth). Abdullāh ibn Amr was very precautious in

preserving this script. Mujāhid, one of his favorite pupils says, I went to

Abdullāh ibn Amr and took in hand a script placed beneath his cushion. He

stopped me. I said, You never save anything from me. He replied:

This is the Sādiqah

(the Script of Truth). It is what I heard from the Holy Prophet ( ). No other narrator intervenes

between him and myself. If this script, the Book of Allāh, and wahaz (his

agricultural land) are secured for me, I would never care about the rest of the

world. [Jāmi Bayān-ul-Ilm]

). No other narrator intervenes

between him and myself. If this script, the Book of Allāh, and wahaz (his

agricultural land) are secured for me, I would never care about the rest of the

world. [Jāmi Bayān-ul-Ilm]

This script remained with his children. His grandson, Amr ibn

Shuaib used to teach the ahādīth

contained in it. Yahyā ibn Main and Ali ibn al-Madini have said that

every tradition reported by Amr ibn Shuaib in any book of hadīth has been taken from this script [Tahdhīb at-Tahdhīb].

Ibn al-Asir says that this script contained one thousand ahādīth. [Asad-ul-Ghābah]

The Script of Anas ( )

)

Sayyiduna Anas ibn Mālik ( )

was one of those companions of the Holy Prophet (

)

was one of those companions of the Holy Prophet ( ) who knew writing. His mother

had brought him to the Holy Prophet (

) who knew writing. His mother

had brought him to the Holy Prophet ( ) when he was ten years old. He

remained in the service of the Holy Prophet (

) when he was ten years old. He

remained in the service of the Holy Prophet ( ) for ten years during which he

heard a large number of ahādīth and wrote them down. Saīd ibn Hilal, one of his

pupils, says,

) for ten years during which he

heard a large number of ahādīth and wrote them down. Saīd ibn Hilal, one of his

pupils, says,

When we insisted upon Anas, may Allāh be

pleased with him, he would bring to us some notebooks and say, These are what

I have heard and written from the Holy Prophet ( ), after which I have presented

them to the Holy Prophet (

), after which I have presented

them to the Holy Prophet ( ) for confirmation.

[Mustadrik Hākim]

) for confirmation.

[Mustadrik Hākim]

It shows that Sayyiduna Anas (

) had

not only written a large number of ahādīth

in several notebooks, but had also showed them to the Holy Prophet (

) had

not only written a large number of ahādīth

in several notebooks, but had also showed them to the Holy Prophet ( ) who had confirmed them.

) who had confirmed them.

The Script of Ali

It is well known that Sayyiduna Ali ( )

had a script of ahādīth with him. He

says,

)

had a script of ahādīth with him. He

says,

I have not written anything from the Holy

Prophet ( ) except the Holy Qurān and

what is contained in this script. [Sahīh

Bukhāri- Book of Jihad]

) except the Holy Qurān and

what is contained in this script. [Sahīh

Bukhāri- Book of Jihad]

Imām Bukhāri has mentioned this script at six different places

of his Sahīh. A combined study of all those places reveals that this

script was substantially large and it consisted of ahādīth

about qisās (retaliation), diyah (blood money), fidyah

(ransom), rights of the non-Muslim citizens of an Islamic state, some specific

kinds of inheritance, zakāh rules pertaining to camels of different

ages, and some rules about the sanctity of the city of Madīnah.

The script was written by Sayyiduna Ali ( )