The Scope of the Prophetic Authority

The verses of the Qur’ân quoted in the previous chapter, and the natural

conclusions derived therefrom, are sufficient to prove the authority of the

“Sunnah” of the Holy Prophet ( ).

Its being a source of Islâmic law stands proved on that score. Yet the Holy

Qur’ân has not only stressed upon the “obedience of the Messenger” as a

general rule or principle. It has also highlighted the different shades of

authority in order to explain the scope of his obedience, and the various

spheres where it is to be applied.

).

Its being a source of Islâmic law stands proved on that score. Yet the Holy

Qur’ân has not only stressed upon the “obedience of the Messenger” as a

general rule or principle. It has also highlighted the different shades of

authority in order to explain the scope of his obedience, and the various

spheres where it is to be applied.

Therefore, we propose in this chapter to deal with each of these spheres

separately, and to explain what the Holy Qur’ân requires of us in respect

of each of them.

The Prophet’s ( ) Authority to

Make Laws

) Authority to

Make Laws

A number of verses in the Holy Qur’ân establish the authority of the

Holy Prophet ( ) as a legislator or a

law-maker. Some of those are reproduced below:

) as a legislator or a

law-maker. Some of those are reproduced below:

And My mercy embraces all things. So I shall prescribe it

for those who fear Allâh and pay zakâh (obligatory alms) and those who have

faith in Our signs; those who follow the Messenger, the unlettered Prophet

whom they find written down in the Torah and the Injîl, and who bids them to

the Fair and forbids them the Unfair, and makes lawful for them the good

things, and makes unlawful for them the impure things, and relieves them of

their burdens and of the shackles that were upon them. So, those who believe

in him, and honour him, and help him, and follow the light that has been sent

down with him- they are the ones who acquire success. (7:156-157)

The emphasized words in this verse signify that one of the functions of the

Holy Prophet ( ) is “to make lawful

the good things and make unlawful the impure things.” This function has been

separated from “bidding the Fair and forbidding the Unfair,” because the

latter relates to the preaching of what has already been established as Fair,

and warning against what is established as Unfair, while the former embodies

the making of lawful and unlawful, that is, the enforcing of new laws

regarding the permissibility or prohibition of things. This function of

prescribing new religious laws and rules is attributed here not to the Holy

Qur’ân, but to the Holy Prophet (

) is “to make lawful

the good things and make unlawful the impure things.” This function has been

separated from “bidding the Fair and forbidding the Unfair,” because the

latter relates to the preaching of what has already been established as Fair,

and warning against what is established as Unfair, while the former embodies

the making of lawful and unlawful, that is, the enforcing of new laws

regarding the permissibility or prohibition of things. This function of

prescribing new religious laws and rules is attributed here not to the Holy

Qur’ân, but to the Holy Prophet ( ).

It, therefore, cannot be argued that the “making lawful or unlawful” means

the declaration of what is laid down in the Holy Qur’ân only, because the

declaration of a law is totally different from making it.

).

It, therefore, cannot be argued that the “making lawful or unlawful” means

the declaration of what is laid down in the Holy Qur’ân only, because the

declaration of a law is totally different from making it.

Besides, the declaration of the established rules has been referred to in

the earlier sentence separately, that is, “bids them to the Fair and forbids

for them the Unfair.” The reference in the next sentence, therefore, is only

to “making” new laws.

The verse also emphasizes “to believe” in the Holy Prophet ( ).

In the present context, it clearly means to believe in all his functions

mentioned in the verse including to make something “lawful” or

“unlawful.”

).

In the present context, it clearly means to believe in all his functions

mentioned in the verse including to make something “lawful” or

“unlawful.”

The verse, moreover, directs to follow the light that has been sent down

with him. Here again, instead of “following the Holy Qur’ân,”

“following the light” has been ordered, so as to include all the

imperatives sent down to the Holy Prophet ( ),

either through the Holy Book or through the unrecited revelation, reflecting

in his own orders and acts.

),

either through the Holy Book or through the unrecited revelation, reflecting

in his own orders and acts.

Looked at from whatever angle, this verse is a clear proof of the fact that

the Holy Prophet ( ) had an authority

based, of course, on the unrecited revelation, to make new laws in addition to

those mentioned in the Holy Qur’ân.

) had an authority

based, of course, on the unrecited revelation, to make new laws in addition to

those mentioned in the Holy Qur’ân.

The Holy Qur’ân says:

Fight those who do not believe in Allâh and the Hereafter

and do not hold unlawful what Allâh and His Messenger have made unlawful.

(9:29)

The underlined words signify that it is necessary to “hold unlawful what

Allâh and His Messenger made unlawful,” and that the authority making

something unlawful is not restricted to Allâh Almighty. The Holy Prophet ( )

can also, by the will of Allâh, exercise this authority. The difference

between the authority of Allâh and that of the Messenger is, no doubt,

significant. The former is wholly independent, intrinsic and self-existent,

while the authority of the latter is derived from and dependent on the

revelation from Allâh. Yet, the fact remains that the Holy Prophet (

)

can also, by the will of Allâh, exercise this authority. The difference

between the authority of Allâh and that of the Messenger is, no doubt,

significant. The former is wholly independent, intrinsic and self-existent,

while the authority of the latter is derived from and dependent on the

revelation from Allâh. Yet, the fact remains that the Holy Prophet ( )

has this authority and it is necessary for believers to submit to it alongwith

their submission to the authority of Allâh.

)

has this authority and it is necessary for believers to submit to it alongwith

their submission to the authority of Allâh.

The Holy Qur’ân says:

No believer, neither man nor woman, has a right, when Allâh

and His Messenger decide a matter, to have a choice in their matter in issue.

And whoever disobeys Allâh and His Messenger has gone astray into manifest

error. (33:36)

Here, the decisions of Allâh and the Messenger ( )

both have been declared binding on the believers.

)

both have been declared binding on the believers.

It is worth mentioning that the word “and” occuring between “Allâh”

and “His Messenger” carries both conjunctive and disjunctive meanings. It

cannot be held to give conjunctive sense only, because in that case it will

exclude the decision of Allâh unless it is combined with the decision of the

messenger- a construction too fallacious to be imagined in the divine

expression.

The only reasonable construction, therefore, is to take the word “and”

in both conjunctive and disjunctive meanings. The sense is that whenever Allâh

or His Messenger ( ), any one or both

of them, decide a matter, the believers have no choice except to submit to

their decisions.

), any one or both

of them, decide a matter, the believers have no choice except to submit to

their decisions.

It is thus clear that the Holy Prophet ( )

has the legal authority to deliver decisions in the collective and individual

affairs of the believers who are bound to surrender to those decisions.

)

has the legal authority to deliver decisions in the collective and individual

affairs of the believers who are bound to surrender to those decisions.

The Holy Qur’ân says:

Whatever the Messenger gives you, take it; and whatever he

forbids you, refrain from it. (59:7)

Although the context of this verse relates to the distribution of the

spoils of war, yet it is the well-known principle of the interpretation of the

Holy Qur’ân that, notwithstanding the particular event in which a verse is

revealed, if the words used are general, they are to be construed in their

general sense; they cannot be restricted to that particular event.

Keeping in view this principle, which is never disputed, the verse gives a

general rule about the Holy Prophet ( )

that whatever order he gives is binding on the believers and whatever thing he

forbids stands prohibited for them. The Holy Qur’ân thus has conferred a

legal authority to the Holy Prophet (

)

that whatever order he gives is binding on the believers and whatever thing he

forbids stands prohibited for them. The Holy Qur’ân thus has conferred a

legal authority to the Holy Prophet ( )

to give orders, to make laws and to enforce prohibitions.

)

to give orders, to make laws and to enforce prohibitions.

It will be interesting here to cite a wise answer of ‘Abdullâh ibn

Mas’űd ( ), the blessed companion

of the Holy Prophet (

), the blessed companion

of the Holy Prophet ( ), which he

gave to a woman.

), which he

gave to a woman.

A woman from the tribe of Asad came to ‘Abdullah ibn Mas’űd ( )

and said, “I have come to know that you hold such and such things as

prohibited. I have gone through the whole Book of Allâh, but never found any

such prohibition in it.”

)

and said, “I have come to know that you hold such and such things as

prohibited. I have gone through the whole Book of Allâh, but never found any

such prohibition in it.”

‘Abdullah ibn Mas’űd ( )

replied, “Had you read the Book you would have found it. Allâh Almighty

says: “Whatever the Messenger gives you, take it; and whatever he forbids

you, refrain from it.” (59:7). (Ibn Mâjah)

)

replied, “Had you read the Book you would have found it. Allâh Almighty

says: “Whatever the Messenger gives you, take it; and whatever he forbids

you, refrain from it.” (59:7). (Ibn Mâjah)

By this answer ‘Abdullah ibn Mas’űd pointed out that this verse is so

comprehensive that it embodies all the orders and prohibitions of the Holy

Prophet ( ) and since the questioned

prohibitions are enforced by the Holy Prophet (

) and since the questioned

prohibitions are enforced by the Holy Prophet ( )

they form part of this verse, though indirectly.

)

they form part of this verse, though indirectly.

The Holy Qur’ân says:

But no, by your Lord, they shall not be (deemed to be)

believers unless they accept you as judge in their disputes, then find in

their hearts no adverse feeling against what you decided, but surrender to it

in complete submission. (4:65)

The authority of the Holy Prophet ( )

established in this verse seems apparently to be an authority to adjudicate in

the disputes brought before him. But after due consideration in the

construction used here, this authority appears to be more than that of a

judge. A judge, no doubt, has an authority to deliver his judgments, but the

submission to his judgments is not a condition for being a Muslim. If somebody

does not accept the judgment of a duly authorized judge, it can be a gross

misconduct on his part, and a great sin, for which he may be punished, but he

cannot be excluded from the pale of Islâm on this score alone. He cannot be

held as disbeliever.

)

established in this verse seems apparently to be an authority to adjudicate in

the disputes brought before him. But after due consideration in the

construction used here, this authority appears to be more than that of a

judge. A judge, no doubt, has an authority to deliver his judgments, but the

submission to his judgments is not a condition for being a Muslim. If somebody

does not accept the judgment of a duly authorized judge, it can be a gross

misconduct on his part, and a great sin, for which he may be punished, but he

cannot be excluded from the pale of Islâm on this score alone. He cannot be

held as disbeliever.

On the contrary, the verse vehemently insists that the person who does not

accept the verdicts of the Holy Prophet ( )

cannot be held to be a believer. This forceful assertion indicates that the

authority of the Holy Prophet (

)

cannot be held to be a believer. This forceful assertion indicates that the

authority of the Holy Prophet ( ) is

not merely that of a customary judge. The denial of his judgments amounts to

disbelief. It implies that the verdicts of the Holy Prophet (

) is

not merely that of a customary judge. The denial of his judgments amounts to

disbelief. It implies that the verdicts of the Holy Prophet ( )

referred to here are not the normal verdicts given in the process of a trial.

They are the laws laid down by him on the basis of the revelation, recited or

unrecited, that he receives from Allâh. So, the denial of these laws is, in

fact, the denial of the divine orders which excludes the denier from the pale

of Islâm.

)

referred to here are not the normal verdicts given in the process of a trial.

They are the laws laid down by him on the basis of the revelation, recited or

unrecited, that he receives from Allâh. So, the denial of these laws is, in

fact, the denial of the divine orders which excludes the denier from the pale

of Islâm.

Looked at from this point of view, this verse gives the Holy Prophet ( )

not only the authority of a judge, but also confers upon him the authority to

make laws, as binding on the Muslims as the divine laws.

)

not only the authority of a judge, but also confers upon him the authority to

make laws, as binding on the Muslims as the divine laws.

The Holy Qur’ân says:

They say, “we believe in Allâh and the Messenger, and we

obey.” Then, after that, a group of them turn away. And they are not

believers. And when they are called to Allâh and His Messenger that he may

judge between them, suddenly a group of them turn back. But if they had a

right, they come to him submissively! Is it that there is sickness in their

hearts? Or are they in doubt? Or do they fear that Allâh may be unjust

towards them, and His Messenger? Nay, but they are the unjust. All that the

believers say when they are called to Allâh and His Messenger that he (the

Messenger) may judge between them, is that they say, “We hear and we

obey.” And they are those who acquire success. And whoever obeys Allâh and

His Messenger and fears Allâh and observes His Awe, such are those who are

the winners. (24:47-52)

These verses, too, hold that, in order to be a Muslim, the condition is to

surrender to the verdicts of the Holy Prophet ( ).

Those who do not turn towards him in their disputes inspite of being called to

him cannot, according to the Holy Qur’ân, be treated as believers. It

carries the same principle as mentioned in the preceding verse: It is the

basic ingredient of the belief in Allâh and His Messenger that the authority

of the Messenger should be accepted whole-heartedly. He must be consulted in

disputes and obeyed. His verdicts must be followed in total submission, and

the laws enunciated by him must be held as binding.

).

Those who do not turn towards him in their disputes inspite of being called to

him cannot, according to the Holy Qur’ân, be treated as believers. It

carries the same principle as mentioned in the preceding verse: It is the

basic ingredient of the belief in Allâh and His Messenger that the authority

of the Messenger should be accepted whole-heartedly. He must be consulted in

disputes and obeyed. His verdicts must be followed in total submission, and

the laws enunciated by him must be held as binding.

The Holy Prophet’s ( )

Authority to Interpret the Holy Qur’ân

)

Authority to Interpret the Holy Qur’ân

The second type of authority given to the Holy Prophet ( )

is the authority to interpret and explain the Holy Book. He is the final

authority in the interpretation of the Holy Qur’ân. The Holy Qur’ân

says:

)

is the authority to interpret and explain the Holy Book. He is the final

authority in the interpretation of the Holy Qur’ân. The Holy Qur’ân

says:

And We sent down towards you the Advice (i.e. the Qur’ân)

so that you may explain to the people what has been sent down to them, and so

that they may ponder. (16:44)

It is unequivocally established here that the basic function of the Holy

Prophet ( ) is to explain the Holy

Book and to interpret the revelation sent down to him. It is obvious that the

Arabs of Makkah, who were directly addressed by the Holy Prophet (

) is to explain the Holy

Book and to interpret the revelation sent down to him. It is obvious that the

Arabs of Makkah, who were directly addressed by the Holy Prophet ( )

did not need any translation of the Qur’ânic text. The Holy Qur’ân was

revealed in their own mother tongue. Despite that they were mostly illiterate,

they had a command on their language and literature. Their beautiful poetry,

their eloquent speeches and their impressive dialogues are the basic sources

of richness in the Arabic literature. They needed no one to teach them the

literal meaning of the Qur’ânic text. That they understood the textual

meaning is beyond any doubt.

)

did not need any translation of the Qur’ânic text. The Holy Qur’ân was

revealed in their own mother tongue. Despite that they were mostly illiterate,

they had a command on their language and literature. Their beautiful poetry,

their eloquent speeches and their impressive dialogues are the basic sources

of richness in the Arabic literature. They needed no one to teach them the

literal meaning of the Qur’ânic text. That they understood the textual

meaning is beyond any doubt.

It is thus obvious that the explanation entrusted to the Holy Prophet ( )

was something more than the literal meaning of the Book. It was an explanation

of what Allâh Almighty intended, including all the implications involved and

the details needed. These details are also received by the Holy Prophet (

)

was something more than the literal meaning of the Book. It was an explanation

of what Allâh Almighty intended, including all the implications involved and

the details needed. These details are also received by the Holy Prophet ( )

through the unrecited revelation. As discussed earlier, the Holy Qur’ân has

clearly said,

)

through the unrecited revelation. As discussed earlier, the Holy Qur’ân has

clearly said,

Then, it is on Us to explain it. (75:19)

This verse is self-explanatory on the subject. Allâh Almighty has Himself

assured the Holy Prophet ( ) that He

shall explain the Book to him. So, whatever explanation the Holy Prophet (

) that He

shall explain the Book to him. So, whatever explanation the Holy Prophet ( )

gives to the Book is based on the explanation of Allâh Himself. So, his

interpretation of the Holy Qur’ân overrides all the possible

interpretations. Hence, he is the final authority in the exegesis and

interpretation of the Holy Qur’ân. His word is the last word in this

behalf.

)

gives to the Book is based on the explanation of Allâh Himself. So, his

interpretation of the Holy Qur’ân overrides all the possible

interpretations. Hence, he is the final authority in the exegesis and

interpretation of the Holy Qur’ân. His word is the last word in this

behalf.

Examples of Prophetic Explanations of the Qur’ân

To be more specific, I would give a few concrete instances of the

explanations of the Holy Book given to us by the Holy Prophet ( ).

These examples will also show the drastic amount of what we lose if we ignore

the sunnah of the Holy Prophet (

).

These examples will also show the drastic amount of what we lose if we ignore

the sunnah of the Holy Prophet ( ):

):

1. The salaah (prayer) is the well-known way of worship which is

undisputedly held as the first pillar of Islâm after having faith. The Holy

Qur’ân has ordered more than 73 times to observe it. Despite this large

number of verses giving direct command to observe the salaah, there is

no verse in the entire Book to explain how to perform and observe it.

Some components of the salaah, like ruku’ (bowing down) or sujud

(prostration) or qiyaam (standing) are, no doubt, mentioned in the Holy

Qur’ân. But the complete way to perform salaah as a composite whole

has never been explained. It is only through the sunnah of the Holy

Prophet ( ) that we learn the exact

way to perform it. If the sunnah is ignored, all these details about

the correct way of observing salaah are totally lost. Not only this,

nobody can bring forth an alternate way to perform salaah on the basis

of the Holy Qur’ân alone.

) that we learn the exact

way to perform it. If the sunnah is ignored, all these details about

the correct way of observing salaah are totally lost. Not only this,

nobody can bring forth an alternate way to perform salaah on the basis

of the Holy Qur’ân alone.

It is significant that the Holy Qur’ân has repeated the comand of

observing salaah as many as 73 times, yet, it has elected not to

describe the way it had to be performed. This is not without some wisdom

behind it. The point that seems to have been made deliberately is one of the

significance of the sunnah.

By avoiding the details about no less a pillar of Islâm than salaah,

it is pointed out that the Holy Qur’ân is meant for giving the fundamental

principles only. The details are left to the explanations of the Holy Prophet

( ).

).

2. Moreover, it is mentioned in the Holy Qur’ân that the salaah

is tied up with some prescribed times. Allâh Almighty says:

Surely, the salaah is a timed obligation for the believers.

(4:104)

It is clear from this verse that there are some particular times in which

the salaah should be performed. But what are those times is nowhere

mentioned in the Holy Qur’ân. Even that the daily obligatory prayers are

five in number is never disclosed in the Holy Book. It is only through the sunnah

of the Holy Prophet ( ) that we have

learnt the exact number and specific times of the obligatory prayers.

) that we have

learnt the exact number and specific times of the obligatory prayers.

3. The same is the position of the number of rak’aat to be

performed in each prayer. It is not mentioned anywhere in the Holy Qur’ân

that the number of rak’aat is two in Fajr, four in Zuhr, ‘Asr and

‘Isha; it is only in the sunnah that these matters are mentioned.

If the sunnah is not believed, all these necessary details even

about the first pillar of Islâm remain totally unknown, so as to render the salaah

too vague an obligation to be carried out in practice.

4. The same is the case if zakaah (alms-giving), the second pillar

of Islâm, which is in most cases combined with the salaah in the Holy

Qur’ân. The order to “pay zakaah” is found in the Holy Book in

more than thirty places. But who is liable to pay it? On what rate it should

be paid? What assets are liable to the obligation of zakaah? What

assets are exempted from it? All these questions remain unanswered if the sunnah

of the Holy Qur’ân ( ) is ignored.

It is the Holy Prophet (

) is ignored.

It is the Holy Prophet ( ) who

explained all these details about zakaah.

) who

explained all these details about zakaah.

5. Fasts of Ramadan are held to be the third pillar of Islâm. Here again

only the fundamental principles are found in the Holy Qur’ân. Most of the

necessary details have been left to the explanation of the Holy Prophet ( )

which he disclosed through his sayings and acts. What acts, other than eating,

drinking and having sex, are prohibited or permitted during the fast? Under

what conditions can one break the fast during the day? What kind of treatment

can be undertaken in the state of fasting? All these and similar other details

are mentioned by the Holy Prophet (

)

which he disclosed through his sayings and acts. What acts, other than eating,

drinking and having sex, are prohibited or permitted during the fast? Under

what conditions can one break the fast during the day? What kind of treatment

can be undertaken in the state of fasting? All these and similar other details

are mentioned by the Holy Prophet ( ).

).

6. The Holy Qur’ân has said after mentioning how to perform wudu’,

(ablution):

And if you are junub (defiled) well-purify yourself. (5:6)

It is also clarified in the Holy Qur’ân that while being junub

(defiled) one should not perform prayers (4:43). But the definition of junub

(defiled) is nowhere given in the Holy Qur’ân nor is it mentioned how

should a defiled person “well-purify” himself. It is the Holy Prophet ( )

who has explained all these questions and laid down the detailed injunctions

on the subject.

)

who has explained all these questions and laid down the detailed injunctions

on the subject.

7. The command of the Holy Qur’ân concerning Hajj, the fourth pillar of

Islâm, is in the following words:

And as a right of Allâh, it is obligatory on people to

perform the Hajj of the House- whoever has the ability to manage his way to

it. (3:97)

It is just not disclosed here as to how many times the Hajj (pilgrimage to

Makkah) is obligatory? The Holy Prophet ( )

explained that the obligation is discharged by performing Hajj only once in a

life-time.

)

explained that the obligation is discharged by performing Hajj only once in a

life-time.

8. The Holy Qur’ân says:

Those who accumulate gold and silver and do not spend them

in the way of Allâh, give them the news of a painful punishment. (9:34)

Here, “accumulation” is prohibited and “spending” is enjoined. But

the quantum of none of the two is explained. Upto what limit can one save his

money, and how much spending is obligatory? Both the questions are left to the

explanation of the Holy Prophet ( )

who has laid down the detailed rules in this respect.

)

who has laid down the detailed rules in this respect.

9. The Holy Qur’ân, while describing the list of the women of prohibited

degree, with whom one cannot marry, has extended the prohibition to marrying

two sisters in one time:

And (it is also prohibited) to combine two sisters together.

(4:23)

The Holy Prophet ( ) while

explaining this verse, clarified that the prohibition is not restricted to two

sisters only. The verse has, instead, laid down a principle which includes the

prohibition of combining an aunt and her niece, paternal or maternal, as well.

) while

explaining this verse, clarified that the prohibition is not restricted to two

sisters only. The verse has, instead, laid down a principle which includes the

prohibition of combining an aunt and her niece, paternal or maternal, as well.

10. The Holy Qur’ân says:

Today the good things have been permitted to you. (5:5)

Here, the “good things” are not explained. The detailed list of the

lawful “good things” has only been given by the Holy Prophet ( )

who has described the different kinds of food being not lawful for the Muslims

and not falling in the category of “good things.” Had there been no such

explanation given by the Holy Prophet (

)

who has described the different kinds of food being not lawful for the Muslims

and not falling in the category of “good things.” Had there been no such

explanation given by the Holy Prophet ( )

everybody could interpret the “good things” according to his own personal

desires, and the very purpose of the revelation, namely, to draw a clear

distinction between good and bad, could have been disturbed. If everybody was

free to determine what is good and what is bad, neither any revelation nor a

messenger was called for. It was through both the Holy Book and the Messenger

(

)

everybody could interpret the “good things” according to his own personal

desires, and the very purpose of the revelation, namely, to draw a clear

distinction between good and bad, could have been disturbed. If everybody was

free to determine what is good and what is bad, neither any revelation nor a

messenger was called for. It was through both the Holy Book and the Messenger

( ) that the need was fulfilled.

) that the need was fulfilled.

Numerous other examples of this nature may be cited. But the few examples

given above are, perhaps, quite sufficient to show the nature of the

explanations given by the Holy Prophet ( )

as well as to establish their necessity in the framework of an Islâmic life

ordained by the Holy Qur’ân for its followers.

)

as well as to establish their necessity in the framework of an Islâmic life

ordained by the Holy Qur’ân for its followers.

Does the Holy Qur’ân Need Explanation?

Before concluding this discussion, it is pertinent to answer a question

often raised with reference to the explanation of the Holy Qur’ân. The

question is whether the Holy Qur’ân needs anyone to explain its contents?

The Holy Qur’ân in certain places seems to claim that its verses are

self-explanatory, easy to understand and clear in their meanings. So, any

external explanation should be uncalled for. Why, then, is the prophetic

explanation so much stressed upon?

The answer to this question is found in the Holy Qur’ân itself. A

combined study of the relevant verses reveals that the Holy Qur’ân deals

with two different types of subjects. One is concerned with the general

statements about the simple realities, and it includes the historic events

relating to the former prophets and their nations, the statement of Allâh’s

bounties on mankind, the creation of the heavens and the earth, the

cosmological signs of the divine power and wisdom, the pleasures of the

Paradise and the torture of the Hell, and subjects of similar nature.

The other type of subjects consists of the imperatives of Sharî’ah,

the provisions of Islâmic law, the details of doctrinal issues, the wisdom of

certain injunctions and other academic subjects.

The first type of subject, which is termed in the Holy Qur’ân as Zikr

(the lesson, the sermon, the advice) is, no doubt, so easy to understand that

even an illiterate rustic can benefit from it without having recourse to

anyone else. It is in this type of subjects that the Holy Qur’ân says:

And surely We have made the Qur’ân easy for Zikr (getting

a lesson) so is there anyone to get a lesson? (54:22)

The words “for Zikr” (getting a lesson) signify that the

easiness of the Holy Qur’ân relates to the subjects of the first nature.

The basic thrust of the verse is on getting lesson from the Qur’ân and its

being easy for this purpose only. But by no means the proposition can be

extended to the inference of legal rules and the interpretation of the legal

and doctrinal provisions contained in the Book. Had the interpretation of even

this type of subjects been open to everybody irrespective of the volume of his

learning, the Holy Qur’ân would have not entrusted the Holy Prophet ( )

with the functions of “teaching” and “explaining” the Book. The verses

quoted earlier, which introduce the Holy Prophet (

)

with the functions of “teaching” and “explaining” the Book. The verses

quoted earlier, which introduce the Holy Prophet ( )

as the one who “teaches” and “explains” the Holy Qur’ân, are

explicit on the point that the Book needs some messenger to teach and

interpret it. Regarding the type of verses which require explanation, the Holy

Qur’ân itself says,

)

as the one who “teaches” and “explains” the Holy Qur’ân, are

explicit on the point that the Book needs some messenger to teach and

interpret it. Regarding the type of verses which require explanation, the Holy

Qur’ân itself says,

And these similitudes We mention before the people. And

nobody understands them except the learned. (29:43)

Thus, the “easiness” of the subjects of the first type does not exclude

the necessity of a prophet who can explain all the legal and practical

implications of the imperatives contained in the Holy Qur’ân.

The Time Limit of the Prophetic Authority

We have so far studied the two types of the Prophetic authority, first

being the authority to make new laws in addition to those contained in the

Holy Qur’ân, and the second being the authority to explain, interpret and

expound the Qur’ânic injunctions.

But before proceeding to other aspects of the Prophetic authority, another

issue should be resolved just here.

It is sometimes argued by those who hesitate to accept the full authority

of the Sunnah, that whenever the Holy Qur’ân has conferred on the Holy

Prophet ( ) an authority to make laws

or to explain and interpret the Book, it meant this authority to be binding on

the people of the Prophet’s (

) an authority to make laws

or to explain and interpret the Book, it meant this authority to be binding on

the people of the Prophet’s ( )

time only. They were under the direct control and the instant supervision of

the Holy Prophet (

)

time only. They were under the direct control and the instant supervision of

the Holy Prophet ( ) and were

addressed by him face to face. Therefore, the Prophetic authority was limited

to them only. It cannot be extended to all the generations for all times to

come.

) and were

addressed by him face to face. Therefore, the Prophetic authority was limited

to them only. It cannot be extended to all the generations for all times to

come.

This contention leads us to the discovery of the time limits of the

Prophetic authority. The question is whether the authority of the Holy Prophet

( ) was confined to his own time, or

it is an everlasting authority which holds good for all times to come.

) was confined to his own time, or

it is an everlasting authority which holds good for all times to come.

The basic question underlying this issue has already been answered in

detail; and that is the question of the nature of this authority. It has been

established through a number of arguments that the obedience of the Holy

Prophet ( ) was not enjoined upon the

Muslims in his capacity of a ruler. It has been enjoined in his capacity of a

prophet. Had it been the authority of a ruler only which the Holy Prophet (

) was not enjoined upon the

Muslims in his capacity of a ruler. It has been enjoined in his capacity of a

prophet. Had it been the authority of a ruler only which the Holy Prophet ( )

exercised, it would logically be inferred that the authority is tied up with

his rule, and as soon as his administrative rule is over, his authority

simultaneously ceases to have effect.

)

exercised, it would logically be inferred that the authority is tied up with

his rule, and as soon as his administrative rule is over, his authority

simultaneously ceases to have effect.

But if the authority is a “Prophetic” authority, and not merely a

“ruling authority,” then it is obvious that it shall continue with the

continuance of the prophethood, and shall not disappear until the Holy Prophet

( ) no longer remains a prophet.

) no longer remains a prophet.

Now, the only question is whether the Holy Prophet ( )

was a prophet of a particular nation or a particular time, or his prophethood

extended to the whole mankind for all times. Let us seek the answer from the

Holy Qur’ân itself. The Holy Qur’ân says:

)

was a prophet of a particular nation or a particular time, or his prophethood

extended to the whole mankind for all times. Let us seek the answer from the

Holy Qur’ân itself. The Holy Qur’ân says:

Say: O mankind! I am the Messenger of Allâh to you all…

(7:158)

And We did not send you (O Prophet) except to the entire

mankind, bearing good news and warning. (34:28)

And We did not send you save as a mercy unto all the worlds.

(21:107)

Blessed be He Who has sent down the Qur’ân on His servant

so that he may be a warner to all the worlds. (25:1)

And We have sent you (O Prophet) for mankind as a messenger.

And Allâh suffices to be a witness. (4:79)

And the whole mankind is addressed when it is said:

O mankind! The Messenger has come to you with the truth from

your Lord, so believe: it is better for you. And if you disbelieve, to Allâh

belongs what is in the heavens and in the earth. And Allâh is All-Knowing,

All-Wise. (4:170)

The first five verses need no elaboration. They are self-explanatory on the

point that the Holy Prophet ( ) was

sent to the whole mankind and not to a particular people; his prophethood was

not limited either in time or in place.

) was

sent to the whole mankind and not to a particular people; his prophethood was

not limited either in time or in place.

The fifth verse addresses the whole mankind and enjoins upon all of them to

believe in the Holy Prophet ( ).

Nobody can say that the belief of the Holy Prophet (

).

Nobody can say that the belief of the Holy Prophet ( )

was restricted to his own time. It is, according to this verse, incumbent upon

all the peoples, of whatever age, to believe in his Prophethood.

)

was restricted to his own time. It is, according to this verse, incumbent upon

all the peoples, of whatever age, to believe in his Prophethood.

It is also mentioned in the Holy Qur’ân that the Holy Prophet ( )

is the last Messenger after whom no Prophet is to come:

)

is the last Messenger after whom no Prophet is to come:

Muhammad is not the father of any one of your men, but the

Messenger of Allâh and the last of the prophets. And Allâh is All-Knowing in

respect of everything. (33:40)

This verse made it clear that the Holy Prophet ( )

is the last one in the chain of prophets. The earlier prophets were often sent

to a particular nation for a particular time, because they were succeeded by

other prophets. But no prophet is to come after Muhammad (

)

is the last one in the chain of prophets. The earlier prophets were often sent

to a particular nation for a particular time, because they were succeeded by

other prophets. But no prophet is to come after Muhammad ( ).

Hence, his prophethood extends to all the nations and all the times. This is

what the Holy Prophet (

).

Hence, his prophethood extends to all the nations and all the times. This is

what the Holy Prophet ( ) himself

explained in the following words:

) himself

explained in the following words:

The Israelites were led by the prophets. Whenever a prophet

would pass away, another prophet would succeed him. But there is no prophet

after me. However, there shall be successors, and shall be in large numbers. (Sahih

al-Bukhari Ch. 50 Hadîth 3455)

If the realm of his prophethood would not reach out to the next

generations, the people of those generations would be left devoid of the

prophetic guidance, while Allâh does not leave any people without prophetic

guidance.

In the light of the verses quoted above, there remains no doubt in the fact

that the Holy Prophet ( ) is a

messenger to all the nations for all times to come.

) is a

messenger to all the nations for all times to come.

If his prophethood extends to all times, there remains no room for the

suggestion that his prophetic authority does no longer hold good and the

present day Muslims are not bound to obey and follow him.

There is another point in the subject worth attention:

It is established through a large number of arguments in the first chapter

that Allâh Almighty sent no divine book without a messenger. It is also

clarified by Allâh that the messengers are sent to teach the Book and to

explain it. It is also proved earlier that but for the detailed explanations

of the Holy Prophet ( ), nobody might

know even the way of obligatory prayers.

), nobody might

know even the way of obligatory prayers.

The question now is whether all these Prophetic explanations were needed

only by the Arabs of the Prophetic age. The Arabs of Makkah were more aware of

the Arabic language than we are. They were more familiar with the Qur’ânic

style. They were physically present at the time of revelation and observed

personally all the surrounding circumstances in which the Holy Book was

revealed. They received the verses of the Holy Qur’ân from the mouth of the

Holy Prophet ( ) and were fully aware

of all the factors which help in the correct understanding of the text. Still,

they needed the explanations of the Holy Prophet (

) and were fully aware

of all the factors which help in the correct understanding of the text. Still,

they needed the explanations of the Holy Prophet ( )

which were binding on them.

)

which were binding on them.

Then, how can a man of ordinary perception presume that the people of this

age, who lack all these advantages, do not need the explanations of a prophet?

We have neither that command on the Arabic language as they had, nor are we so

familiar with the Qur’ânic style as they were, nor have we seen the

circumstances in which the Holy Qur’ân was revealed, as they have seen. If

they needed the guidance of the Holy Prophet ( )

in interpreting the Holy Qur’ân, we should certainly need it all the more.

)

in interpreting the Holy Qur’ân, we should certainly need it all the more.

If the authority of the Holy Qur’ân has no time-limit, if the text of

the Qur’ân is binding on all generations for all times to come, then the

authority of the Messenger, which is included in the very Qur’ân without

being limited to any time bond, shall remain as effective as the Holy Qur’ân

itself. While ordaining for the “obedience of the messenger,” the Holy

Qur’ân addressed not only the Arabs of Makkah or Madînah. It has addressed

all the believers when it was said:

O those who believe, obey Allâh and obey the Messenger and

those in authority among you. (4:59)

If the “obedience of Allâh” has always been combined with the

“obedience of the Messenger” as we have seen earlier, there is no room for

separating any one from the other. If one is meant for all times, the other

cannot be meant for a particular period. The Holy Qur’ân at another place

has also warned against such separation between Allâh and His Messenger:

Those who disbelieve in Allâh and His Messengers, and

desire to make separation between Allâh and His Messengers and say, “We

believe in some and disbelieve in some,” desiring to adopt a way in between

this and that—those are the unbelievers in truth; and We have prepared for

the disbelievers a humiliating punishment. (4:150-151)

Therefore, the submission to the authority of the Holy Prophet ( )

is a basic ingredient of having belief in his prophethood, which can never be

separated from him. Thus, to accept the prophetic authority in the early days

of Islâm, and to deny it in the later days, is so fallacious a proposition

that cannot find support from any source of Islâmic learning, nor can it be

accepted on any touchstone of logic and reason.

)

is a basic ingredient of having belief in his prophethood, which can never be

separated from him. Thus, to accept the prophetic authority in the early days

of Islâm, and to deny it in the later days, is so fallacious a proposition

that cannot find support from any source of Islâmic learning, nor can it be

accepted on any touchstone of logic and reason.

The Prophetic Authority in Worldly Affairs

Another point of view often presented by some westernised circles is that

the authority of the Holy Prophet ( )

is, no doubt, established by the Holy Qur’ân even for all the generations

for all times to come; But, the scope of this authority is limited only to the

doctrinal affairs and the matters of worship. The function of a prophet,

according to them, is restricted to correct the doctrinal beliefs of the ummah

and to teach them how to worship Allâh. As far as the worldly affairs are

concerned, they are not governed by the prophetic authority. These worldly

affairs include, in their view, all the economic, social and political affairs

which should be settled according to the expediency at each relevant time, and

the Prophetic authority has no concern with them. Even if the Holy Prophet (

)

is, no doubt, established by the Holy Qur’ân even for all the generations

for all times to come; But, the scope of this authority is limited only to the

doctrinal affairs and the matters of worship. The function of a prophet,

according to them, is restricted to correct the doctrinal beliefs of the ummah

and to teach them how to worship Allâh. As far as the worldly affairs are

concerned, they are not governed by the prophetic authority. These worldly

affairs include, in their view, all the economic, social and political affairs

which should be settled according to the expediency at each relevant time, and

the Prophetic authority has no concern with them. Even if the Holy Prophet ( )

gives some directions in these fields, he does so in his private capacity, and

not as a Messenger. So, it is not necessary for the ummah to comply

with such directions.

)

gives some directions in these fields, he does so in his private capacity, and

not as a Messenger. So, it is not necessary for the ummah to comply

with such directions.

To substantiate this proposition, a particular tradition of the Holy

Prophet ( ) is often quoted, though

out of context, in which he said to his companions:

) is often quoted, though

out of context, in which he said to his companions:

You know more about your worldly affairs.

Before I quote this tradition in its full context, the very concept upon

which this proposition is based needs examination.

In fact, this view is based on a serious misconception about the whole

structure of the Islâmic order.

The misconception is that Islâm, like some other religions, is restricted

only to some doctrines and some rituals. It has no concern with the day-to-day

affairs of the human life. After observing the prescribed doctrines and

rituals, everybody is free to run his life in whatever way he likes, not

hindered in any manner by the divine imperatives. That is why the advocates of

this view confine the Prophetic authority to some doctrines and rituals only.

But, the misconception, however fashionable it may seem to be, is a

misconception. It is an established fact that Islâm, unlike some other

religions which can coincide and co-exist with the secular concept of life, is

not merely a set of doctrines and rituals. It is a complete way of life which

deals with the political, economic and social problems as well as with

theological issues. The Holy Qur’ân says,

O those who believe, respond to the call of Allâh and His

Messenger when he calls you for what gives you life. (8:24)

It means that Allâh and His Messenger call people towards life. How is it

imagined that the affairs of life are totally out of the jurisdiction of Allâh

and His Messenger? Nobody who has studied the Holy Qur’ân can endorse that

its teachings are limited to worship and rituals. There are specific

injunctions in the Holy Qur’ân about sale, purchase loans, mortgage,

partnership, penal laws, inheritance, matrimonial relations, political

affairs, problems of war and peace and other aspects of international

relations. If the Islâmic teachings were limited to the doctrinal and ritual

matters, there is no reason why such injunctions are mentioned in the Holy

Qur’ân.

Likewise the sunnah of the Holy Prophet ( )

deals with the economic, social, political and legal problems in such detail

that voluminous books have been written to compile them. How can it be

envisaged that the Holy Prophet (

)

deals with the economic, social, political and legal problems in such detail

that voluminous books have been written to compile them. How can it be

envisaged that the Holy Prophet ( )

entered this field in such detailed manner without having any authority or

jurisdiction? The injunctions of the Holy Qur’ân and sunnah in this

field are so absolute, imperative and of mandatory nature that they cannot be

imagined to be personal advices lacking any legal force.

)

entered this field in such detailed manner without having any authority or

jurisdiction? The injunctions of the Holy Qur’ân and sunnah in this

field are so absolute, imperative and of mandatory nature that they cannot be

imagined to be personal advices lacking any legal force.

We have already quoted a large number of verses from the Holy Qur’ân

which enjoin the obedience of Allâh and the Messenger ( )

upon the believers. This “obedience” has nowhere been limited to some

particular field. It is an all-embracing obedience which requires total

submission from the believers, having no exception whatsoever.

)

upon the believers. This “obedience” has nowhere been limited to some

particular field. It is an all-embracing obedience which requires total

submission from the believers, having no exception whatsoever.

It is true that in this field, which is termed in the Islâmic law as “mu’âmalât,”

the Holy Qur’ân and sunnah have mostly given some broad principles

and left most of the details open to be settled according to ever-changing

needs, but in strict conformity with the principles laid down by them. Thus

the field not occupied by the Qur’ân and sunnah is a wider field

where the requirements of expediency can well play their role. But it does not

mean that the Qur’ân and sunnah have no concern with this vital

branch of human life which has always been the basic cause of unrest in the

history of humanity, and in which the so-called “rational views” mostly

conflicting with each other, have always fallen prey to satanic desires

leading the world to disaster.

Anyhow, the fallacy of this narrow viewpoint about Islâm which excludes

all the practical spheres of life from its pale, rather, to be more correct,

makes them devoid of its guidance, cannot sustain before the overwhelming

arguments which stand to rule it out totally.

The Event of Fecundation of the Palm-Trees

Let me now turn to the tradition which is often quoted to support this

fallacious view. The details of the tradition are as follows:

The Arabs of Madînah used to fecundate their palm-trees in order to make

them more fruitful. This operation was called ta’bîr which is

explained by E. W. Lane (Arabic English Lexicon) as below:

“He fecundated a palm-tree by means of the spadix of the male tree, which

is bruised or brayed, and sprinkled upon the spadix of the female; or by

inserting a stalk of a raceme of the male tree into the spathe of the female,

after shaking off the pollen of the former upon the spadix of the female.”

Keeping this in view, read the following tradition, as mentioned by Imâm

Muslim in his Sahîh:

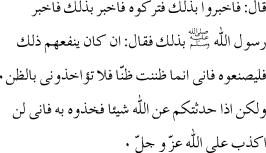

The blessed companion Talhâ ( )

says:”I passed along with the Holy Prophet (

)

says:”I passed along with the Holy Prophet ( )

across some people who were on the tops of the palm-trees. The Holy Prophet (

)

across some people who were on the tops of the palm-trees. The Holy Prophet ( )

asked, ‘What are they doing?’ Some people said, ‘They are fecundating

the tree. They insert the male into the female and the tree stands

fecundated.’ The Holy Prophet (

)

asked, ‘What are they doing?’ Some people said, ‘They are fecundating

the tree. They insert the male into the female and the tree stands

fecundated.’ The Holy Prophet ( )

said, ‘I do not think it will be of any use.’ The people (who were

fecundating the trees) were informed about what the Holy Prophet (

)

said, ‘I do not think it will be of any use.’ The people (who were

fecundating the trees) were informed about what the Holy Prophet ( )

said. So, they stopped this operation. Then the Holy Prophet (

)

said. So, they stopped this operation. Then the Holy Prophet ( )

was informed about their withdrawal. On this, the Holy Prophet (

)

was informed about their withdrawal. On this, the Holy Prophet ( )

said, ‘If it is in fact useful for them, let them do it, because I had only

made a guess. So, do not cling to me in my guess. But when I tell you

something on behalf of Allâh, take it firm, because I shall never tell a lie

on behalf of Allâh.”

)

said, ‘If it is in fact useful for them, let them do it, because I had only

made a guess. So, do not cling to me in my guess. But when I tell you

something on behalf of Allâh, take it firm, because I shall never tell a lie

on behalf of Allâh.”

According to the blessed companion Anas ( ),

the Holy Prophet (

),

the Holy Prophet ( ) has also said on

this occasion:

) has also said on

this occasion:

You know more about your worldly affairs.

The words of this tradition, when looked at in its full context, would

clearly reveal that the Holy Prophet ( )

in this case did not deliver an absolute prohibition against the fecundation

of the palm trees. There was no question of its being lawful or unlawful. What

the Holy Prophet (

)

in this case did not deliver an absolute prohibition against the fecundation

of the palm trees. There was no question of its being lawful or unlawful. What

the Holy Prophet ( ) did was neither

a command, nor a legal or religious prohibition, nor a moral condemnation. It

was not even a serious observation. It was only a remark passed by him by the

way in the form of an instant and general guess, as he himself clarified

later. “I do not think it will be of any use.” Nobody can take this

sentence as a legal or religious observation. That is why the Holy Prophet (

) did was neither

a command, nor a legal or religious prohibition, nor a moral condemnation. It

was not even a serious observation. It was only a remark passed by him by the

way in the form of an instant and general guess, as he himself clarified

later. “I do not think it will be of any use.” Nobody can take this

sentence as a legal or religious observation. That is why the Holy Prophet ( )

did not address with it the persons involved in the operation, nor did he

order to convey his message to them. It was through some other persons that

they learned about the remark of the Holy Prophet (

)

did not address with it the persons involved in the operation, nor did he

order to convey his message to them. It was through some other persons that

they learned about the remark of the Holy Prophet ( ).

).

Although the remark was not in the form of an imperative, but the blessed

companions of the Holy Prophet ( )

used to obey and follow him in everything, not only on the basis of his legal

or religious authority, but also out of their profound love towards him. They,

therefore, gave up the operation altogether. When the Holy Prophet (

)

used to obey and follow him in everything, not only on the basis of his legal

or religious authority, but also out of their profound love towards him. They,

therefore, gave up the operation altogether. When the Holy Prophet ( )

came to know about their having abstained from the operation on the basis of

what he remarked, he clarified the position to avoid any misunderstanding.

)

came to know about their having abstained from the operation on the basis of

what he remarked, he clarified the position to avoid any misunderstanding.

The substance of his clarification is that only the absolute statements of

the Holy Prophet ( ) are binding,

because they are given in his capacity of a prophet on behalf of Allâh

Almighty. As for a word spoken by him as a personal guess, and not as an

absolute statement, it should be duly honoured, but it should not be taken as

part of Sharî’ah.

) are binding,

because they are given in his capacity of a prophet on behalf of Allâh

Almighty. As for a word spoken by him as a personal guess, and not as an

absolute statement, it should be duly honoured, but it should not be taken as

part of Sharî’ah.

As I have mentioned earlier, there is a vast field in the day-to-day

worldly affairs which is not occupied by the Sharî’ah, where the

people have been allowed to proceed according to their needs and expedience

and on the basis of their knowledge and experience. What instruments should be

used to fertilise a barren land? How the plants should be nourished? What

weapons are more useful for the purpose of defence? What kind of horses are

more suitable to ride? What medicine is useful in a certain disease? The

questions of this type relate to the field where the Sharî’ah has

not supplied any particular answer. All these and similar other matters are

left to the human curiosity which can solve these problems through its

efforts.

It is this unoccupied field of mubâhat about which the Holy Prophet

( ) observed:

) observed:

You know more about your worldly affairs.

But it does not include those worldly affairs in which the Holy Qur’ân

or the sunnah have laid down some specific rules or given a positive

command. That is why the Holy Prophet ( ),

while declaring the matter of the palm-trees to be in the unoccupied field,

has simultaneously observed, “But when I tell you something on behalf of Allâh,

take it firm.”

),

while declaring the matter of the palm-trees to be in the unoccupied field,

has simultaneously observed, “But when I tell you something on behalf of Allâh,

take it firm.”

The upshot of the foregoing discussion is that the sunnah of the

Holy Prophet ( ) is the second source

of Islâmic law. Whatever the Holy Prophet (

) is the second source

of Islâmic law. Whatever the Holy Prophet ( )

said or did in his capacity of a Messenger is binding on the ummah.

This authority of the sunnah is based on the revelation he received

from Allâh. Hence, the obedience of the Holy Prophet (

)

said or did in his capacity of a Messenger is binding on the ummah.

This authority of the sunnah is based on the revelation he received

from Allâh. Hence, the obedience of the Holy Prophet ( )

is another form of the obedience of Allâh. This prophetic authority which is

established through a large number of Qur’ânic verses, cannot be curtailed,

neither by limiting its tenure, nor by exempting the worldly affairs from its

scope.

)

is another form of the obedience of Allâh. This prophetic authority which is

established through a large number of Qur’ânic verses, cannot be curtailed,

neither by limiting its tenure, nor by exempting the worldly affairs from its

scope.

![]()